- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

Shahana Page 3

Shahana Read online

Page 3

Chapter 5

In the morning, the boy wakes shouting, his eyes clenched shut as if against some horror. He struggles to sit up, but falls back on the mattress. Shahana rushes to him. Have they rescued a mad boy? ‘Chup, chup, quiet, you are safe.’

The boy throws out his arms and Shahana jumps back. ‘Open your eyes. We will not hurt you.’ She speaks in Pahari but it has no effect. She tries Urdu. ‘You are safe.’

The boy quietens; his eyes open. They are grey like Irfan’s, and Shahana’s breath catches in her throat.

‘Where are you from?’ She blinks, as if to stop the memories.

The boy stares at Shahana and Tanveer. ‘Who will you tell?’

Shahana snorts. ‘Do you think we will be telling anyone about you?’ She tries another question. ‘Which language were you speaking in the night?’

The boy looks surprised. ‘Koshur, Kashmiri.’ He adds, ‘I am from a village in the Kashmir Valley. Not far from the LoC.’

Tanveer asks, ‘What is your good name?’

The boy hesitates a moment, then says, ‘Zahid Amir Kumar.’

‘So you are Muslim, like us,’ Tanveer says.

The boy tilts his head in affirmation.

‘Why are you here?’ Shahana asks.

Zahid’s eyes flicker and a shadow falls across his face.

‘What am I doing?’ Shahana says quickly, sorry she asked. ‘We must get you something to eat, some chai. Then you will feel better.’

Zahid manages to sit up and looks around the room. His face is pale, as if he will faint.

Shahana fills the samovar with water and tea leaves. Zahid lets out a small breath. ‘I am looking for my father,’ he says, as if Shahana has only just asked her question. ‘He disappeared three years ago. We used to live in Srinagar then. My mother sat in a park every month with a sign in Angrezi, English, that said, “Where are our missing husbands and sons?”’

‘Why in Angrezi?’ Tanveer asks.

‘The women wanted the world to know what was happening. Maybe a journalist would take a picture. But very few journalists came.’

Shahana thinks of Aunty Rabia. Does she wait for her husband to come home? Even to find out he died would be better for her. Then she would be the esteemed widow of a martyr.

Zahid continues. ‘The Indian soldiers came in a van and took him away. They would have interrogated him. They would have—’ He breaks off as Shahana shakes her head and glances at Tanveer.

‘What did the soldiers do?’ Tanveer asks anyway.

With a measured glance at Shahana, Zahid says, ‘They would have kept him in prison, perhaps.’

‘Then you could visit him?’

‘We don’t know which one. Maybe they let him go.’

‘Then he would have come home?’

Shahana can see the annoyance well up in Zahid’s face and she shushes Tanveer. But Zahid answers him. ‘I have seen men who have been interrogated. Sometimes they do not remember who they are.’ Then he glances at Shahana and says, ‘Sometimes they die. I just need to know.’

Tanveer is quiet, though Shahana can see he’d like to ask more questions. Even at his age he recognises sorrow, and there is no need to talk. Shahana does what her mother would have done: she cooks roti.

Zahid manages to swallow some of the warm bread and drink his chai. Shahana smiles at him. She won’t be dressing a corpse anytime soon. Then her smile fades. It is strange how he has managed to cross the Line of Control.

It is Tanveer who asks what Shahana is thinking. ‘So how did you cross over the LoC? There are mines between the two electric fences, and razor wire.’

Zahid answers too quickly and Shahana looks up from her chai. ‘I came across the river.’

‘The big river, the Neelum?’ Shahana asks.

‘We call it the Kishanganga.’

‘So you can swim,’ Tanveer says, awe in his tone. But Shahana knows it would take more than a strong swimmer to cross the Neelum. It would take a miracle.

‘Not very well,’ Zahid admits. ‘The river pulled me under and spat me out. Where you found me,’ he adds.

‘You were fortunate,’ Shahana says, thinking of her father. ‘The river kills in more ways than drowning.’

‘There are Indian and Pakistani soldiers,’ Tanveer adds. ‘Our father—’ He stops himself, then asks, ‘Why didn’t they see you?’

‘It was night-time, there was no moon,’ Zahid says.

Shahana shoots him a swift glance. The soldiers see everything, even at night. Nana-ji told her they have motion sensors and thermal imaging devices that they carry with them in the dark. Their father was shot at night.

Zahid’s eyes hold knowledge, and a certain wariness. ‘Perhaps it is different travelling in this direction?’ he says.

Shahana thinks that is possible. The Indian soldiers on the other side may have thought her father was a militant, but who would mind on this side if a jihadi militant returned home? Though she has heard that the army has been warned to watch out for terrorists. The problem is, whether a man is a militant or a terrorist depends on which side you are on. She glances at Zahid again. Anyone can see Zahid is not a militant. He looks just like a jawan, a teenaged boy.

Later, when both boys are asleep, Shahana opens Nana-ji’s trunk and takes out his white embroidered cap and shoes. She kneels there, thinking, then carefully puts them back. What if Zahid is not just an innocent jawan? She would wait and see if he is worthy to wear Nana-ji’s shoes.

Chapter 6

When Shahana wakes in the morning, Tanveer is gone. She peers over the edge of the charpoy. Zahid is not on the mattress either. Her heart beats like a drum and nausea rises before she realises she can’t hear Rani’s bell under the house. The milk is in a pot on the floor. The boys must be out finding firewood. Usually Tanveer is asking questions when she wakes. It is a peaceful feeling to wake alone.

She stretches and winces; her back aches this morning. She will have a wash in the spring. Who knows how long the weather will hold? She hasn’t had a proper wash since Eid ul Fitr in the early autumn. There was no joy at Eid, no one to visit and share food with, though she tried to make it fun for Tanveer. At least they had fish to eat and prayed together.

She takes her soap and towel and a clean set of clothes. She has only a few outfits. She even unpicked one of Nana-ji’s, managing to get an outfit for Tanveer out of it, too. It is a pity her mother’s beautiful clothes burned in the fire.

The spring bubbles at her. A fowl, with a turquoise and gold head, fluffs up its feathers on a rock. She can’t stop thinking about Tanveer. Have the boys gone together? Will Zahid watch out for him? She quickly peels off the shalwar she has worn and slept in for weeks, washes and dries her lower half, then pulls on a clean one. She does the same with her qameez. She untwists the plait at her back and shakes out her hair. As she puts her head under the water, she flinches – it is even colder on her head. Her head aches but she rubs the soap in and rinses it out. It would be good to have shampoo, but she has to keep her money for food and medicine. When she went to school her mother washed her hair every Friday with Gloss shampoo. After school she and Ayesha would pretend they were hairdressers, brushing each other’s hair. Now, whenever Shahana combs her hair much of it is left on the comb.

She washes her dirty outfit in the spring, bangs it on a rock then spreads it on a bush to dry. She is plaiting her hair when the boys return with Rani.

Zahid is limping and Shahana feels a pang that he has no shoes. He helps Tanveer lift the basket of firewood from Rani’s back. Normally women collect the firewood in baskets on their heads and men sew, but everything in their lives is upside down now.

Tanveer chats, but Zahid is quiet and pale. ‘I showed Zahid where we catch the best fish.’ He gives a little jump.

Shahana’s hand stills on her plait. ‘You went near the big river?’

‘Not too close.’ He grins at her.

Shahana frowns at Zahid. She can’t decide if he is not strong enoug

h yet to walk on the mountain or if something has upset him. She quickly finishes the plaiting and gathers her things together. ‘Come inside,’ she says. ‘I will make roti for breakfast.’

Her comb slips out of her hand and Zahid picks it up. It is something Irfan would have done. ‘Shukriya,’ she murmurs her thanks. His kindness disturbs her; it would be easier if he weren’t kind, easier to send him away. She knows he should leave as soon as he is well enough. An unrelated male cannot stay in the house, she imagines her mother warning her. But Shahana is not sure she wants him to leave – she hasn’t seen Tanveer this happy for so long. The thought of her brother calms her. Tanveer will always be there; she and Zahid will never be alone.

‘Did you milk Rani?’ she asks Zahid as they walk along the logs up to the door. Tanveer still hasn’t learned how.

He nods, and she thanks him again.

‘Your house is built high,’ he says. ‘Our house in Srinagar was too, in case the lake flooded.’

‘Ours is for the snow,’ Shahana says. ‘If we didn’t build high with a space underneath the house, the snow would trap us for months.’

‘Like Eskimos.’ Zahid smiles.

Shahana stares at him. His teeth look white and even, like her father’s. Zahid looks almost a man. How can she possibly keep him there?

Tanveer’s chatter brings her back to her surroundings. ‘What are Eskimos?’

‘People who live at the North Pole,’ Zahid says. ‘They live with snow all around them – not just on the top of a mountain.’

Tanveer’s questions come thick and fast. Shahana fills the samovar, then cooks flatbread on the stones around the fire. Soon they will have to cut grass and dry it for the floor, before it gets much colder.

She glances over at the boys. ‘Zahid,’ she says when there is a lull in their conversation. ‘When we go to the village you could wear a shawl over your face, wear my clothes.’ She is thinking of the shalwar qameez she made from Nana-ji’s outfit, though she suspects it won’t fit him.

‘No!’ He stands, then pauses, as if catching his breath. ‘I couldn’t do that,’ he says more quietly.

‘You don’t want to be seen, do you? You don’t have any papers. People may think you are a fugitive.’ She doesn’t like the way her voice sounds, as though she doesn’t believe him. But what if he lied?

His face whitens as if he is sick again. ‘In that case,’ he says, ‘I will not go to the village.’

‘Someone may come up here and see you.’

‘Does everyone in this area know you?’

‘Possibly.’ Now, her mother scolds. Now is the time to tell him to leave.

‘Zahid,’ she says, then stops.

Tanveer catches on to the conversation. ‘He can stay.’ He says it loudly, as if Shahana is already telling Zahid to go, then turns to Zahid. ‘You won’t leave us?’

Zahid is quiet as he watches Shahana.

A knot of fear forms in Shahana’s chest. He can’t stay, but how can she send him away? Winter is close. An image of Nana-ji gasping for breath in the cold night lodges in her mind.

She sighs, ignoring the voices in her head. ‘You can be our cousin from Muzaffarabad. We have some family there, though we’ve not seen them since we were small.’

‘A brother might be better.’ For a moment there is a playful glint in Zahid’s eyes. It is not seemly for him to stay – no, no, her mother shouts – but they need him. Nana-ji died at the end of last winter and Shahana is not sure she can get through another without help.

‘Everyone knows our brother is dead,’ she says dully.

Zahid’s expression changes. ‘I am sorry. I didn’t mean to upset you.’

Tanveer isn’t daunted. ‘You’re just like him – that’s why we want you to stay.’

Shahana takes the bread off the stones and lays it on tin plates. It’s not true, she says to herself. Zahid is not ‘just like’ Irfan. His eyes are the same, his skin, too, but his nose is straighter, his hair darker.

The room is quiet while they eat. There is a little fish left and Shahana gives it to Zahid to help him grow stronger.

When he is finished Zahid looks as if he will collapse as he lies on the mattress. She should tell him to sleep under the house with Rani, but it will be cold. She’ll wait until he is better.

‘We can go up the mountain. We could catch game,’ Zahid says slowly.

‘And we can take our grandfather’s rifle,’ Tanveer says without looking at Shahana.

She presses her lips together. She has never wanted Tanveer to touch that rifle. Look at what has happened to them because of weapons. Nana-ji said the culture of the gun has replaced the Kashmiri culture of peace and tolerance. He called it Kashmiriyat.

‘The rifle will only be used to obtain food, to give us life.’ Zahid is leaning on his elbow, his gaze on Shahana, and she knows Tanveer has talked of the rifle.

What if she gives Zahid the rifle and he runs off, or shoots Tanveer? ‘No,’ she says.

There is a silence that even Tanveer doesn’t break.

Shahana explains, ‘You must understand – we have had much trouble. We are the only ones left in our family.’

The shadow fills Zahid’s face again and Shahana is ashamed of her distrust. Everyone has had trouble. She tries to say she is sorry, that she knows Zahid must have sorrow too, but he stops her.

‘Shahana, you have taken me into your home, you have fed me. While I am here I will be your family. I will be like a brother to you and to Veer.’

Veer? Shahana starts at the nickname. When did they become so close?

Tanveer jumps up and shouts. ‘Alhamdulillah, praise be to God.’

Shahana doesn’t share his jubilation, for she has caught the words Tanveer has missed. While I am here.

Chapter 7

They climb the slope; more trees have burst into fire. Shahana loves the trees aflame but dreads what will follow. The leaves are falling; soon winter will be here.

Tanveer carries the bag they use to put fish in. Shahana has her backpack with her embroidery in it. While the boys chase a wild musk goat or hare she must sit and get some work done or she will never make enough money for all three of them.

Tanveer runs ahead and Zahid calls him back before Shahana can. ‘Hoi, Veer, we don’t want to frighten off our khana, our food.’

Shahana waits under a chinar tree and takes out her sewing. Chinar trees are special to their valley – the Moghul emperors planted them. She can see the boys moving further up the mountain.

Zahid seems so well now, she thinks. He hardly limps and there is no sign of the dog sickness, no sudden bursts of anger or drooling, though he argued with her before they left about the rifle. Tanveer took his side. ‘How will we catch prey without a gun, Shahji?’ he complained.

She hears a shot and stops sewing. Never will she get used to that sound. Was it a soldier? She quickly puts away her work and waits, but the boys don’t return. Even when she stands she can’t see them. She hears a man’s shout further away. What has happened? Just as she starts up the slope, the boys come rushing down.

‘Run!’ Zahid says without stopping.

‘What is it?’ she asks.

‘Jaldi ao, come quickly.’

Soon they reach thick bushes. They burrow under them and catch their breath.

‘What did you see?’ Shahana asks Tanveer.

‘Militants.’

Shahana’s whole body stiffens, but the thumping in her chest is loud and fast. Militants are not always evil men, but it was militants who caused the trouble when Irfan and their mother died. Those militants had left. A new group must have come to train in the mountains.

‘What did they look like?’ she asks, trying to ignore the galloping in her chest.

‘They had turbans and full beards like Pakistani tribal men,’ Tanveer says.

Shahana glances at Zahid. He has said nothing about the militants. There is sweat on the hairs of his young moustache. He is pale and pulls

in his breath like Tanveer does when he has a breathing attack.

‘Zahid? Are you hurt?’ she asks. Maybe he is not as well as she thought.

He is shaking and she moves closer.

‘Did they shoot at you?’ Was that the shot she heard?

‘No,’ Tanveer says. He also is watching Zahid.

Finally Zahid says, ‘I can’t let them see me.’ His voice sounds as if it’s been stretched too far.

‘Why?’ Shahana asks. ‘Surely they won’t shoot children?’

‘They’ll know I am from across the LoC.’

‘How can they know this? You look like us.’

Zahid stares at her miserably and she catches her tongue between her teeth. She knows there is something he is not saying; she has known it since that first night.

‘Come,’ she says then. ‘They are not following.’

Tanveer has a dead hare in his bag. ‘I ran it down,’ he says, displaying it proudly when they reach the house. Shahana can see that its blood has been drained in the proper way. ‘It would have been easier with the rifle,’ Tanveer adds, and Shahana can hear the reproach in his tone.

She doesn’t comment but catches Zahid glancing at her as he takes out his knife. They watch Zahid skin the hare, remove the organs and cut it into pieces. Then Shahana takes the meat inside.

While she cooks it in a pot over the fire with onions and spices, thoughts crowd her mind like monkeys chattering. Is it safe to let Zahid stay with them? She knows if she asks him, he will shut his mouth. She will have to be patient, but she will watch him carefully.

When she lights the lamp the boys tie up Rani under the house and come inside.

‘Mmm,’ Tanveer says. ‘This hare is tasty.’ He seems to have forgotten the run down the slope to safety, or perhaps he has learned Shahana’s trick of shutting unpleasant things out. She thinks of the stone princess, still etched into the mountain, and sighs. She knows what it feels like to be made of stone. If only stone held firm against fear.

Regardless of her concerns about Zahid, Shahana decides she must thank him. It is the first time they have had meat since Nana-ji died. She says shukriya, but he just inclines his head. She watches him as he eats; he glances up at her but looks away. His fear is palpable. What isn’t he telling her? That the militants could hurt them? She knows that already.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

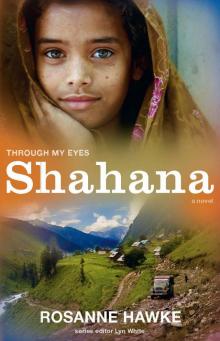

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf