- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

Shahana Page 2

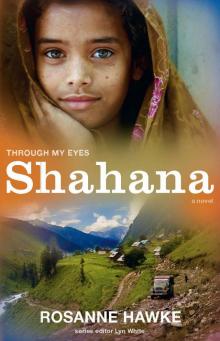

Shahana Read online

Page 2

‘And some rice, please,’ Shahana says. Mr Pervaiz pours a jugful from the big hessian sack into a paper bag and weighs it.

‘Seven rupees, fifty paisa,’ Mr Pervaiz says.

Shahana counts the money out. She lets Tanveer help. He has to learn how to count or he will be cheated in the bazaar. Mr Pervaiz throws a bunch of coriander into her backpack. At least coriander is so cheap it can be given away. She smiles politely at Mr Pervaiz as they leave. He has a concerned look on his face, as though he wants to ask her how she is, but he just lifts his hand in farewell.

She stops at a stall selling second-hand clothes, for she has seen a woollen cap. It has ears like a leopard and costs one rupee. ‘Here,’ she says to Tanveer. ‘This will keep your head warm, since winter is coming. Now you will look like a chitta.’ He puts it on quietly and she sighs. It is so hard to make him laugh. The children selling apples are still sitting by the road. Shahana takes out a rupee. The children look as if they need it. A boy not much older than Tanveer hands her two apples. ‘Shukriya, thank you,’ she says. Behind the children she can see a mound of rubbish with grass growing over it. She pulls Tanveer away before he notices. The mound is where their family home used to be.

At the edge of the village they pass her friend Ayesha’s house with its shiny tin roof and small satellite dish, slanted like a hat. Shahana wishes she could talk to Ayesha, but ever since Ayesha’s father disappeared, her mother has been called a half-widow, and hasn’t opened the door to Shahana. She is too sad and ashamed.

Chapter 3

Shahana wakes to the faint sound of the azan, the call to prayer from the little village mosque. Being careful not to disturb Tanveer, she prays, then takes the plastic bucket outside to milk the goat.

‘Rani, what would we do without you?’ Shahana rests her forehead on Rani’s flank for a moment but she doesn’t relax her fingers. Given the chance, Rani would kick that bucket and the milk would be lost. It is the best milk for Tanveer. When he was younger she gave him buffalo milk but it made him so sick he couldn’t breathe. She had thought he would die. It was Aunty Rabia who had suggested the goat, back when she wasn’t a half-widow.

Rani bleats as Tanveer comes outside to relieve himself. He crouches on the ground away from Shahana, then stands to tie the cord of his shalwar. He seems to have forgotten the noises in the night and pets Rani as she nibbles his qameez.

Shahana finishes the milking. ‘We’ll have some roti and chai.’

He smiles. ‘And then we’ll go to the little river?’

‘Ji, yes.’ He loves the little river, which is just a tributary, but Shahana never feels safe there. It is close to the fast-flowing Neelum River and the Line of Control, with Pakistani and Indian soldiers each patrolling their side of the fence. Besides, there are too many memories.

‘Let’s go close to the big river. It’s where the best fish are. Maybe we’ll even see a chitta,’ Tanveer says.

‘It’s too early for chittas and besides, we won’t be there long. As soon as we catch a fish we’ll come home.’ Her words are a warning and Tanveer’s smile fades. Shahana feels mean but she has to teach him to be careful.

After their bread and chai, Tanveer takes a cloth bag from the hook behind the door and gives it to Shahana. Nana-ji’s rifle is behind the door too, but Shahana has forbidden him to touch it. He races down under the house and slings Nana-ji’s fishing net over his shoulder.

Tanveer runs all the way down the slope. Shahana groans. He’ll probably be wheezing by the time they get there. But when she catches up with him at the little river, Tanveer is happily up to his knees in the water. They are too close to the big river for Shahana’s comfort; she can see the razor wire of the Line of Control fence looming above the riverbank.

Tanveer shouts over the noise of the water. ‘I can see one! It’s shining – a big rainbow trout.’

Nana-ji taught Tanveer how to catch fish. Shahana watches the net fly through the air as he throws it just as Nana-ji used to.

She blinks as Tanveer calls out, ‘I have it! Help me, Shahji.’

Shahana grabs one side of the net and pushes it underwater to meet his hands, which are holding the other side. Even though the little river is a tributary and not as fast as the blue Neelum, the water is cold and strong, and she has to dig her feet into the dirt and pebbles to keep upright. They drag the net and the fish onto the stony bank.

‘How beautiful he is,’ Tanveer says.

‘If we take anything from its natural environment it will lose its shine and joy.’ It is something their mother said. Shahana likes repeating things her mother told her; it makes her feel she is taking good care of Tanveer.

‘Yes, but we have need of you, King Trout.’ Tanveer sits cross-legged beside it on the grass and lets it die naturally, the way Nana-ji said. He murmurs, ‘Bismillah, in the name of God,’ even though he doesn’t have to for a fish. Shahana hands him the cloth bag. The fish will feed them for a few days at least.

They make their way back up the slope under the chinar trees, their broad three-pointed leaves shining orange and red, like silken flames. The forest looks as if it is on fire. Shahana breathes in the fresh sharpness of the fir trees nearby. Tanveer carries the fish and he starts to tell a story. ‘We are children of the Moghul emperor and we have just been fishing in the royal lake. Now we glide home on the lake in a beautiful shikara. My oar is shaped like a heart and I row between the water gardens, when all of a sudden the boat—’

A dog barks, then another. Shahana and Tanveer climb quickly to keep away from the wild dogs. Tanveer looks down to the little river and beyond it, to the Neelum. ‘Those dogs . . .’

‘Do not worry,’ Shahana says. ‘They won’t catch us up here.’ She hopes her words hold true.

‘Shahji, look, it’s a boy. By the big river.’

Shahana stops and shades her eyes. How can Tanveer see that far?

‘A boy?’

‘He’s not fighting the dogs.’

Shahana sees a shape lying on the ground and wonders if the boy is dead. A wave of nausea washes over her. ‘What can we do? We cannot help him.’ She begins to climb again.

‘We have to, Shahji. What if it was Irfan? Or Abu?’

She stares at Tanveer in shock. He hardly ever mentions their father or brother. He is standing with his legs apart like a man.

She hesitates; always she has tried to avoid going near the Neelum. ‘Teik hai, okay. We shall see what we can do, but you keep behind me. I do not want you bitten by a wild dog. What if they have the dog sickness?’

‘Maybe we can throw the net over them,’ Tanveer ventures, sounding like a young boy again.

‘That will just make them angry.’ She picks up a stick and leans on it to test its strength. ‘This should do.’

Tanveer bites his lip. ‘You will be careful?’

‘Certainly, and you keep hold of that fish.’ She hopes the dogs don’t smell it.

There are five dogs circling the body. They look like wolves, dark, though one is yellow. Shahana suspects they are Bakarwal dogs, left behind when the nomads moved their sheep and goats away from the fighting. One dog rushes to the body and worries it; another barks for its turn. How can she help? They sound so fierce. She tries not to look at the body. It only makes her think of that other time. Is Tanveer remembering it too?

‘Tanveer, fetch some stones from the river. Show me how far you can throw them.’

Shahana waits until Tanveer reaches the river and collects some stones from the shore. Then he takes a run-up, like a cricketer. The first stone lands wide. The next produces a yelp, then a growl.

‘Keep throwing,’ Shahana shouts, then she charges down the slope screaming and holding the stick high. When she reaches the dogs only three remain. She hits one and it retreats to a safe distance but one of Tanveer’s stones chases it further. Then another one runs. The yellow dog bares its teeth and holds its ground but Shahana whacks it over the head. The stick breaks. Shahana stands

motionless; the dog snarls and edges closer. Then zing, a stone thumps into its chest, and another. With a yelp, the dog jumps away.

Shahana has seen enough corpses to know the boy doesn’t have the look of death. She yells for Tanveer. ‘Jaldi, quickly, we have to take him before they come back.’ Two of the dogs are a long way off, but they are circling in the manner of wolves planning to sneak up on their prey.

‘Bring the net,’ Shahana cries.

Tanveer spreads it on the ground next to the boy and she lays her woollen shawl over it. They manage to roll the boy so the net and shawl are under him. ‘Now, pull!’

It is not easy. Maybe down the slope they could have easily dragged a dead weight like the boy, but not uphill. At least once they are across the stony riverbank, the grass is smooth. The first time they take a rest, two of the dogs are close behind them; one is the yellow dog that held its ground by the river. Shahana can see the rushing Neelum River and the fence of the Line of Control, where the river changes direction. ‘Pull! Pull, Tanveer!’

The yellow dog snarls at the net. It is too close to the boy’s feet; he isn’t wearing shoes. Shahana shouts at the dog but this does no good. It edges closer, snarling. It bares its teeth at Shahana but she doesn’t know who it will attack first.

Just then a single shot rings out. Shahana drops the net and grabs Tanveer. She was crazy to say they could come near the big river. What was she thinking? Even if the dogs don’t attack them, they will be shot.

Tanveer struggles in her grip. ‘Shahji, it’s okay, look!’

Shahana kneels up to check. It is true – the yellow dog is dead and the other has gone. The threat has disappeared.

‘A soldier must have helped us,’ Tanveer says.

Shahana doesn’t think so. Perhaps a sniper was aiming for them and hit the dog instead. But there is no need to worry Tanveer; she forces herself to smile. ‘Alhamdulillah, praise be to God.’

Then she vomits on the grass.

Chapter 4

It takes all morning, with many rests, to haul the boy home. ‘Help me drag him up to the door,’ Shahana says. This will be the hardest part yet. Rani edges closer and nuzzles the boy’s shalwar, but Tanveer shoos her away. A few centimetres at a time they pull the boy up the log ramp.

Shahana slips inside and lays the cotton mattress from their charpoy onto the floor, then they drag the boy in and roll him onto it. She puts a blanket on their string bed for them to sleep on that night. At least they have Nana-ji’s quilt. Shahana takes it out of the clothes trunk and lays it over the boy.

‘Get some water, Tanveer.’ He races to the spring with a bucket while Shahana brings the fire to life in the hollow in the dirt floor. When Tanveer returns she fills the samovar with water and puts live coals in its central chimney to heat it. She takes water in a cup to the boy and urges him to drink, but his mouth is slack.

‘At least we can keep him warm,’ Tanveer says. He squats beside the boy on the namdah, the felt rug Shahana has embroidered with wool, and they both watch him. Tanveer looks wistful but Shahana is frowning. Tanveer was right about Irfan. The boy looks about fifteen – the same age their brother was when they saw him last, that day he was walking her to school. She closes her eyes a moment. The boy has pale skin like their family, too. Maybe he is from Azad Kashmir and has just got lost. But why is he hurt? Perhaps he fell in the river, or hit his head and was washed up. She checks his head but there is no injury. When she lifts his qameez, there is no blood on his body. Only on his leg there is a wound where the dogs nipped him.

When the water is boiled she washes the boy’s face then rolls up his shalwar and cleans the gash on his leg. She puts salt on it and binds it with a clean rag. She doesn’t know what else to do. There is no medicine in their house except the special tablets and spray for Tanveer in case his breathing grows raspy.

‘What if the dog that bit him was sick?’ Tanveer whispers, as if the boy can hear him.

‘Then we cannot help him,’ she murmurs.

‘Shahji,’ Tanveer says quietly. ‘The net is ripped.’ He doesn’t say what Shahana is thinking. How will we catch fish with a torn net?

Shahana tries to sound brave for her brother. ‘I will repair it,’ she says.

Tanveer slips out to collect firewood and fallen chinar leaves. ‘Ao, come, Rani.’ He takes her with him so she can carry the wood in a basket on her back, like a horse. Shahana picks up her embroidery in a daze, forgetting to remind him to stay nearby. She must do it, whether she feels like it or not, so they can buy food, and string to fix the net. Her grandfather said that the quality of stitching does not differ between the times you feel joy in your work and when you don’t. It is advice that has helped her through many a hard week’s labour.

While she stitches, she broods. Who is the boy? And if he gets better what will she do with him? If Irfan or her parents were alive they would know what to do. She can’t take him to Aunty Rabia, for she won’t open her door. Nor can she take him to Mr Nadir. He’d probably sell the boy to a factory. But she mustn’t keep him in the house. What if someone found out she had an unrelated male staying with them? They would think she had a relationship with him and that is haram, forbidden.

The setting sun casts a shadow from the mountains Sharda and Nardi, and Shahana lights the oil lamp. It is cooler in the evenings now, but the gas bottle ran out a month after Nana-ji died and she has never had enough money to fill it. Many times she and Tanveer are cold at night, even with Nana-ji’s quilt. She hopes the fire will warm the room enough for the boy.

She tries to put him out of her mind while she cuts up the fish for their curry and cooks it in the pan over the fire. She adds garlic, an onion, cumin, cinnamon, salt, some aloo, potatoes, and yoghurt that she has made from Rani’s milk. If only she had some tamarind; her mother often cooked fish in tamarind paste. She leaves the pan by the fire to keep warm while she boils the rice in the dekshi, the cooking pot. Trout is a special dish so she puts a tiny pinch of saffron in the rice to colour it. When she has no saffron she uses turmeric instead. Her mother always said to use food while you had it and God would provide more.

Shahana sighs; she can’t forget the boy. If he had been able to walk she could have directed him to the village mosque. She and Tanveer can’t take him anywhere else now; it was so much effort getting him to the house.

When the food is ready she calls Tanveer. Her tone is sharper than she wants it to be but she can’t help it. Tanveer says ‘bismillah’ and they eat together. Tanveer sucks the fish’s head. ‘So tasty,’ he says. ‘Pity we can’t give the boy some.’ He stares over at the mattress with such yearning that Shahana is afraid for him. Even if the boy survives, he will not be the brother Tanveer longs for.

‘We will feed him tomorrow,’ she says. Her voice sounds firmer than she feels, for she thinks the boy will die in the night. His chest is barely moving. It was like that when she and Tanveer found their father, except they couldn’t drag him to the house; she was only eleven, Tanveer seven. He was down by the Neelum River, near the suspension bridge that crosses to the other side. Some people could get a permit to walk to the middle of the bridge and meet relatives. But their father didn’t want to stay on the bridge: he wanted to cross to the other side of Kashmir to sell his shawls. He didn’t want to work for Mr Nadir anymore, not once Mr Nadir began using young boys to work for him through debt bondage.

They found their father in the evening lying in a pool of blood on the stones by the river. He must have managed to crawl back across the bridge. Whether he had been targeted or just in the line of fire they never knew. Shahana begged him to wake up. ‘Abu, Abu-ji, don’t leave us,’ she cried, not knowing if he could hear her above the roar of the river. Tanveer cried too. When their father realised they were there, he stretched out a hand and touched them each on their heads; then his hand dropped. He didn’t manage to say a word but he had given them a blessing. Some men carried him to Nana-ji’s house so he could be washed ready for buri

al the next morning.

She hopes Tanveer will not be too upset if the boy dies. Although he rarely mentions Irfan, Shahana knows how much he misses him. She does too. There isn’t a day when she doesn’t think of Irfan and how much easier it would be if he were here looking after them. She sighs deeply. If the boy dies, she will just have to go to the village and ask a man to take him to the mosque. But will they believe that he had only just come?

That night, Shahana wakes from a dream of snarling dogs surrounding her, moaning and snapping at her legs. Tanveer is still asleep – she can hear his uneven breathing – but the snapping and moaning is in the room with her. She lights a candle and drops down beside the boy. He is rolling his head from side to side too fast, muttering words. Shahana scoops some water into a cup and tries to pour some down his throat. A little goes in his mouth and the rest spills onto the mattress. The night is not warm and yet he feels so hot to her touch. She tries cooling his face with a wet cloth, and the thrashing gradually stops. His eyes are shut but he says words Shahana doesn’t understand. He says them louder and Shahana glances at Tanveer, hoping he doesn’t wake.

She sings softly, This is Paradise, the flower carpets and fresh rosebuds, the buds tie a knot in the heart. It is a tune her mother sang. Shahana is not sure she has the words right but her mother said Emperor Jahangir wrote them in a poem. He thought Kashmir was Paradise.

The boy’s breathing becomes deeper. She lays her hand on his chest and watches it rise and fall. Maybe he will survive after all. She climbs onto the charpoy with Tanveer. This will be different from her father and Irfan. She finds herself hoping the boy will not die, even though she will have more trouble than she first thought. This she knows because he is not from Azad Kashmir. He speaks a different language: a language from Jammu and Kashmir – the other side of the Line of Control.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf