- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

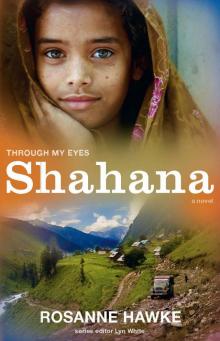

Shahana

Shahana Read online

TITLES IN THIS SERIES

Shahana (Kashmir)

Amina (Somalia)

Naveed (Afghanistan)

Emilio (Mexico)

Malini (Sri Lanka)

Faris (Syria)

THROUGH MY EYES

series editor Lyn White

Shahana

ROSANNE HAWKE

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

A portion of the proceeds (up to $5000) from sales of this series will be donated to UNICEF. UNICEF works in over 190 countries, including those in which books in this series are set, to promote and protect the rights of children. www.unicef.org.au

First published in 2013

Copyright © Text, Rosanne Hawke, 2013

Copyright © Series concept and series creator, Lyn White 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from

the National Library of Australia – www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 246 9

eISBN 978 1 74343 1276

Teachers notes available from www.allenandunwin.com

Cover and text design by Bruno Herfst & Vincent Agostino

Set in 10.5pt Plantin

For the children of conflict;

may you dream without fear.

If Paradise exists on the planet Earth

It is here, it is here, it is here.

NUR AD-DIN ABD AR-RAHMAN JAMI,

as quoted by Emperor Jahangir

upon seeing Kashmir

True peace is not merely the absence

of tension: it is the presence of justice.

It is love that will save our world and

our civilisation, love even for enemies.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Author’s note

Timeline

Glossary

Find out more about …

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

The early sun was shining as Shahana skipped down the village bazaar. Her beloved big brother Irfan was taking her to the tent school. Their cement school had never been rebuilt after the earthquake. Shahana had on her blue qameez and white shalwar; she was nine and had just learned how to iron her school uniform. Today would be exciting: she had two new apples in her backpack, one for herself and one for Ayesha, her friend from the next class.

‘Assalamu alaikum, peace be upon you,’ called Mr Pervaiz from his shop with the new glass windows. ‘Wa alaikum assalam, and upon you be peace,’ Irfan responded. They stopped by the door and Mr Pervaiz gave them each a toffee. He pinched Shahana on the cheek. ‘What an angel,’ he said.

Just as Irfan drew her away towards the road there was a thump from an RPG; then the shelling started. Mr Pervaiz’s new windows burst like a bubble. Glass sprayed over the road and Irfan pushed Shahana to the ground, dropping to cover her.

Shahana wakes up gasping. She hasn’t dreamed this dream for a long time. Dreams are never true, she reminds herself, but she can’t stop the memory, can’t stop her heart racing, as if a black leopard is chasing her. It wasn’t just Irfan: her mother was there too, and her little brother, Tanveer, who has hated loud noises ever since that day. Ever since, his breathing has been worse, as though something sharp stuck in his chest. The banging of the guns went on forever. She could see Tanveer screaming in her mother’s arms, even though she couldn’t hear him. And when the gunfire stopped, Irfan didn’t get up. Nor did her mother.

It was her father who found Shahana and Tanveer. He wept as he took them to Nana-ji, her mother’s father, who lived in the forest. Their own wooden house in the village had burned with the gunfire. Shahana never went back to school after that. Instead, she did all her mother’s jobs and looked after Tanveer. She wishes she could study again but there is no school in the village now, and besides, she can’t make money at school.

Shahana can still hear the gunfire. Is it following her waking hours now, too? Her heart is still beating wildly; she will feel dizzy next. She takes a deep breath to slow the thumping.

Tanveer wakes with a cry. They sleep in the same charpoy, a string bed, and she puts an arm around him. ‘Chup, quiet, it will stop soon.’ She hopes it will, for she realises now that the gunfire is real. It is coming from down near the big Neelum River, where the Line of Control runs along the border between Azad Kashmir and Jammu and Kashmir. A dog howls.

‘See,’ she says, ‘the soldiers are just frightening the dogs away.’ But Shahana isn’t so sure. There is supposed to be a ceasefire on the Line of Control. Indian soldiers patrol the electric fence to stop militants infiltrating their side of Kashmir, and Pakistani soldiers patrol it to keep an eye on the Indian soldiers, but both sides take shots at each other across the high razor wire. Pity anyone who gets in the way.

She takes more slow breaths to steady herself and shuts her mind against the thought. It is too much for one night. Tanveer takes shallow little breaths. When he cries he finds it hard to breathe.

‘Tomorrow we will go to the village.’ Shahana strokes the hair away from Tanveer’s temples and feels his breathing ease. She covers him with the cotton-filled quilt and lies down, facing him, even though she can’t see him. In his hand she can feel the tiny carved camel Nana-ji made for him. It has a separate calf inside, yet Nana-ji carved it out of one piece of wood. It rattles as Tanveer moves his arm under the quilt.

Tanveer is only nine and looks younger. He can’t milk the goat yet, but at least he can collect wood in the forest for their cooking fire. Even then, she has to fight an urge to go with him. He tends to wander and forget where he is; what if he gets lost or falls in the river? He is the only family she has left. She knows she loves him but it is so difficult to feel it, to feel like a mother. Sometimes Shahana feels like the legendary stone princess, who was so beautiful that two princes both wanted to marry her. She prayed that they would all be turned to stone, so the princes wouldn’t kill each other. When Shahana’s heart isn’t pounding, it is cold like stone.

Chapter 2

Shahana hurries to pack the embroidery she has done for Mr Nadir at the cloth shop. If she is late she might not get paid fo

r her work, and she needs the money to buy vegetables, and medicine for Tanveer.

‘Shahji?’

Shahana smiles. It is what Tanveer has called her since he was little.

He pokes his head around their carved door. ‘Are we going to the village yet?’

‘Ji hahn, yes.’ She puts the last dupatta, a long silk scarf, into her backpack and stands up. ‘Rope up Rani, Tanveer.’ She watches him from the doorway as he ties the goat under the house. Rani shakes her head and bleats in time to her bell.

‘A jao, come, let’s go.’ Shahana walks down the log ramp as Tanveer skips up to her. They pass their grandfather’s roses, and the spring where they wash their plates and pots. The water slaps onto the rocks and white froth flies up.

Tanveer runs ahead and swivels to look at her. ‘You’re slow, Shahji.’ It is not raining today, although the grass is wet and slippery; soon there will be slush from snow to walk through. She is about to warn him to be careful when his face changes. The grin disappears. ‘Look.’ He points up the mountain behind them. ‘There’s a big dog.’

‘It’s probably wild. Ignore it, Tanveer.’

He keeps twisting to see the dog as they make their way down the forest path on the mountain slope. ‘Stop worrying about it, Tanveer. We must hurry.’

‘You don’t like them either.’ It sounds like an accusation. She takes his hand until they come to the log bridge over the stream. Here they have to walk in single file.

The bridge is made up of two logs reaching from one bank to a rock in the middle of the stream and another two logs joining the rock to the other side. Planks of wood are nailed across the logs. Every time they put their feet down, the planks groan and shudder. Glancing down, Shahana can see the white water clawing up to the bridge. The roar of the water is almost as loud as the Neelum River. She hesitates, but Tanveer pulls her forward. Shahana tries to think logically. Grown men heavier than her use this bridge every day and it holds them. She gives Tanveer a smile as he looks back at her; no need to show him her fear.

They reach the dirt road that leads to the village. They don’t come this way often, so there are many things to capture Tanveer’s attention. They pass almond trees, and fences made of logs. A man smacks his horse with a piece of leather to make it move. It carries two heavy baskets of wood across its back, although it doesn’t look much stronger than Rani. Some children are sitting by the roadside selling apples. If there is money left Shahana will buy one for Tanveer on the way home. They pass houses pockmarked from shelling and gunfire, and smelly gutters, where Tanveer screws up his nose. Finally, they stand outside Mr Nadir’s shop. It is the only shop in the village that doesn’t show signs of the fighting, for he has enough money to fix it. If Irfan were alive he would bring the embroidery and Shahana wouldn’t have to do business with a man like Mr Nadir.

It is early, so there are no customers inside. The counter has a computer on it, and stacked around the walls are many carpets and namdah rugs made from felt. Shahana puts the backpack on the counter in front of Mr Nadir. He moves some papier-mâché boxes and carved wooden plates out of the way. Shahana’s gaze follows the boxes. She has one, in the shape of a heart. It was her mother’s. Her father found it after the fighting. She chases the thought away with a little shake of her head, and her round silver earrings jingle. They, too, were her mother’s.

Mr Nadir doesn’t say anything at first. He puts his cigarette between his last two fingers and carefully lifts out a dupatta. He checks the tiny stitches around the border, then he takes out the red pashmina shawl, the side panels embroidered with orange thread. Shahana has tried especially hard with the chinar tree pattern. The shawl looks like the forest when the leaves change colour. Mr Nadir grunts.

Shahana holds Tanveer’s hand so he remembers to stay silent. She watches Mr Nadir’s face. It is difficult to tell whether he is pleased or disappointed.

He takes out the other dupattas. ‘Accha,’ he finally says, ‘it is good enough.’ His praise is grudging but Shahana lets out a breath.

Mr Nadir stares at her. ‘You are Zafir’s granddaughter in talent, it seems. More skilful than your father at least.’ His tone darkens as he speaks of her father. He has never said anything like this to her before and she doesn’t know how to reply. Nor does she like the look in his eyes. She stares at the counter to avoid them.

He reaches under the counter and brings out a grey woollen robe. ‘Soon I will need to sell embroidered pherans for the winter. You can try this one in green thread. If you do a good job I will give you silver thread to use.’ He takes a skein from the glass case under the counter. ‘Just embroider here and here.’

Shahana tries not to show how pleased she is to hear of the silver thread. Nana-ji had taught her how to embroider a pheran. Some of the shawls and pherans that Mr Nadir had given Nana-ji to do were stitched by her, especially when his eyes failed before he died last winter. Mr Nadir had never guessed.

Mr Nadir measures the green thread out carefully. ‘Do not lose any.’ The sharpness in his tone makes her tighten her grip on Tanveer’s hand. ‘Or it will come out of your pay.’

His gaze lingers on Tanveer. ‘Does he have your family talent too? His fingers are just the right size for making carpets. He can work for me.’ Mr Nadir tilts his head to the door behind him. Shahana looks up at him in horror. Mr Nadir uses the boys who are sold to him to work on his carpet loom. They also weave the shawls that Shahana embroiders. Their families can’t find the money to buy the boys back. She could never think of selling Tanveer to Mr Nadir.

She shakes her head and tries to speak calmly. ‘Nay, janab, he helps me look after the goat, and collects firewood. I cannot spare him.’

Mr Nadir sneers at her. ‘You will bring him one day. You cannot survive here in Azad Kashmir by yourselves.’ His voice takes on a speculative tone. ‘How old are you now?’

Shahana doesn’t answer but asks for her payment instead. Mr Nadir counts out the rupees. It isn’t as much as Nana-ji received for the same amount of work but it will be enough for their food. She puts the pheran and thread into her backpack and steers Tanveer out of the shop. She won’t bring him next time.

‘I could sew as well as you and Nana-ji,’ Tanveer says.

Shahana smiles at him. ‘I’m sure you will. You just have to keep practising.’ Already he has a flair for colour, and she has taught him the simple stitches Nana-ji started her on.

Tanveer skips ahead. There aren’t many proper shops left in the tiny bazaar. Like the school, many haven’t been rebuilt since the earthquake, and that was years ago. Shahana was only seven then. After that came more fighting; always there has been fighting. There was so much on the day she was born, the forest caught fire.

Tanveer stops outside the teashop. Some men are inside, drinking chai. The teashop is one of the few places in the village with a satellite dish, and the TV is showing the morning news. ‘Let’s watch,’ Tanveer says.

Shahana hesitates, as she always does. It is a man’s place and she can’t go inside. Her mother once told her that before Kashmir was divided between Pakistan and India, women and men worked and prayed together, but it is different now. Shahana decides it won’t hurt to watch from the window; Tanveer has little to fill his mind. Other times they have seen Angrezi, English cartoons, cricket matches or programs on how to pray.

A pretty lady with a shawl over her hair, just like Shahana’s, is speaking. ‘This morning in Srinagar men are throwing stones,’ the lady says. A boy not much older than Shahana appears on the screen. ‘We don’t want conflict. We want azadi, freedom from the Indian forces and foreign militants. We want to govern ourselves. I throw stones not to hurt but to tell the army and militants to leave Kashmir.’

The footage shows men and boys throwing stones at soldiers in the streets. There is much shouting, and the soldiers fire their weapons.

‘I could throw stones a long way too,’ Tanveer says. He has never been allowed to throw stones and Shahana pulls him a

way. A jeep full of Pakistani tourists roars down the bazaar, taking them to one of the bigger villages. They may be the last visitors before the weather closes the valley.

‘Come, we must buy our food.’ Shahana guides Tanveer past the chickens in cages and goat meat hanging on hooks. All the best cuts of meat will have been bought by now, but she doesn’t even check. Her embroidery money is not enough for meat. At Eid when her parents were both alive they had lamb or goat chops cooked in milk, saffron and herbs. Her mother decorated them with pure silver leaf.

They pass the clay pots and stop at Mr Pervaiz’s shop, a stall he sets up outside his house.

‘Assalamu alaikum, Shahana, Tanveer.’ Mr Pervaiz nods at them.

‘Wa alaikum assalam,’ Shahana gives the required response. Mr Pervaiz has sold vegetables to her family since long before she was born.‘Some of your best onions, potatoes and beans, janab,’ she says in the same way her mother used to. Nana-ji said if you have rice and greens, you have everything you need. He said that’s what their family had eaten for generations, even though he always bought meat for Shahana and Tanveer to eat.

When Mr Pervaiz tells her the amount, she argues. ‘But that is twice the usual price. You know I have little money.’ How dare he try to force more from her! If only Nana-ji were here.

Mr Pervaiz spreads his hands. ‘I am truly sorry but there has been fighting on the road near the LoC.’ He spells out the Angrezi letters that everyone uses to refer to the Line of Control. ‘Trucks cannot easily get through, and the one that did charged me danger money. I have to recoup it.’

Shahana knows it is Mr Pervaiz’s son-in-law who brings him goods to sell, but Mr Pervaiz truly looks sorry. She sighs and buys fewer onions than usual. Perhaps they can survive with one onion in their curry. Fortunately, she still has aniseed, cardamom and cinnamon. She has some cumin left too – that is the flavour she thinks is tastiest. She buys the tiniest bit of saffron to colour the rice yellow. Tanveer likes that. Mr Pervaiz hands her the saffron in a twist of paper.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf