- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

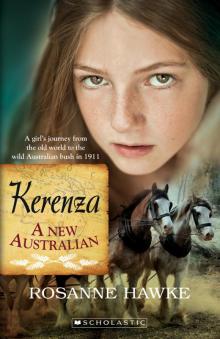

Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Read online

Also in the A New Australian series

Bridget

Sian

Teresa

Frieda

May Tang

Teachers’ notes for Kerenza are available from

www.scholastic.com.au

For Makayla, Amelia, Isaac, Amos, Markus and Xavier, and in memory of Annie (nee Wormald) and Harry Trevilyan, your great-great-grandparents.

I also wish to acknowledge the traditional custodians, the Ngawait people, who once walked on, sang songs and cared for this land for all their descendants who still carry that memory and connection.

Imperial measurements are used in this book. Here are some conversions to show the Metric equivalent.

Length

1 mile = 1.609 kilometres

160 miles = 257 kilometres

1 yard = 0.9144 metres

1 inch = 25.4 millimetres

Area

1 acre = 4046.86 square metres

Capacity

1 gallon = 4.5461 litres

Weight

1 pound = 0.4536 kilograms

Temperature

100°F = 37.7°C

32°F = 0°C

Table of Contents

Cover

Also in the A New Australian series

Title Page

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Acknowledgments

Copyright

1

‘Kerenza! Come back here! You have to pack your trunk.’ Wenna’s calling me, but I won’t go to her. I’ve had enough of packing and looking after Kitto. I race away from my sister, down the cobbled street, past the chapel and past my friend Maylene, who waves at me, but I don’t even stop for her. I turn into the lane to the stile and climb over it into Penponds woods. This is my favourite place. I walk under the huge trees and sit beside the stream. It bubbles and gurgles past my feet, and the sound calms my breathing.

I take out the saffron bun Aunty Dorcas gave me after chapel. She makes the best buns, with real saffron from purple crocus flowers she grows in her garden. If Kitto was here he would want some too. I eat it all and lick the sugar from my fingers. Then I lie back where the bluebells grow in May and watch the sky. It’s easy to see since the trees have lost their leaves. There is hardly any sun today and the clouds billow up. I see a cloud that looks just like Willow my cat, and then it changes into a lion. Roar. I wish I could roar – then everyone would stop and listen to me.

Maybe it will snow again, but I’ll miss it. I’ll miss everything. Josiah Renfrey works at Mr Polglase’s stables and he said he’d let me hold the reins in the sulky again. Mr Polglase is our landlord, and Wenna works in his house, Ivy Cottage. I visit her there after school and pet the foals in the stables. She’s sparkin’ with Josiah. I’ll miss him and the foals. I’ll miss Maylene at school; we do everything together. We even wear our hair the same – if I wear braids so does she. The two of us had an afternoon tea for our eleventh birthday together, like twins. And then there’s Nanny. What will I do without her? She hugs me whenever I get in trouble. She loves me even when I’m naughty.

It’s Da who finds me, not that I’m lost. He sits beside me, watching the stream.

‘I don’t want to pack,’ I say in case he hasn’t heard.

He nods. ‘I don’t want to either.’

I sit up next to him. ‘Truly?’

He smiles at me. ‘I will miss Cornwall too, but the mine is closing and I won’t have any more work. We can’t earn enough here to have land of our own, but in Australia we can have a farm and animals. It will be an adventure.’

I glance at the trees all around us. ‘I’ve always wished I could live in the woods.’ Then I say what is also worrying me. ‘I don’t want to go on the ship.’

Da looks at me, surprised. ‘But you was on Granda’s fishing boat many a time.’

‘This one is big.’ I don’t say how huge the sea is.

‘Well all be there.’

‘Not Maylene,’ I say. ‘Not Nanny.’

He’s quiet when I say that. Then he stands up. ‘Come on. It’s only a six-week trip on a steamship. Since when has a big Cornish girl like you been scared of an adventure?’

I take his hand and he leads me back home to the packing. Elowen has already finished her little trunk and she watches me. ‘Where were you? I wanted you to help me fold my clothes.’ She’s only six and I should be kind, but I don’t feel like answering as I sit in front of my open trunk. I fold my clothes and put them in with Eddie my bear and two books Wenna gave me. I’ll put my scrap album in last after I’ve written in it. The cat jumps in. ‘Hop out, Willow.’ I pick her up and bury my cheek against her whiskers. ‘Poor Willow – I wish you could come too, but you’d suffocate in the trunk.’ Elowen takes her from me so I can finish. I don’t show Elowen the tears in my eyes.

Just then we hear voices in the kitchen. Wenna must be helping Mam pack our crockery. We can hear Wenna because she’s shouting. ‘I’m seventeen! Where will I get such a good job in South Australia? I’m not leaving Josiah. We love each other, and if I go to Australia I’ll never see him again.’

Mam is quiet but Elowen cries. I put my arms around her. ‘Isn’t Wenna coming with us, Krenza?’

The shock of it makes me quiet like Mam, even though the tears run down my face. No Nanny and now no Wenna? Why doesn’t Mam argue with her and make her come?

Sunday, Nineteenth of February, 1911 This is it then. I am leaving Cornwall. This is the last time I can write in my scrap album before the trunk gets locked ready for the steamship. Da is excited about going to South Australia, so is Kitto, but I’m not. Nanny and Wenna aren’t even coming.

I’ve never been on the wide open sea before and I’m sure Australia will be horrible. There are so many wild animals and snakes. To top it off Da is buying the land with Uncle Malachi, who’s already picked it out, and we’ll have to live with our Australian cousins who I’ve never seen before. The only good thing is we’ll have woods and a stream of our own.

Kerenza Trevail,

Fore Street,

Camborne,

Cornwall,

British Empire,

The World.

2

The steamship Armadale is even bigger than I imagined. It has a huge black funnel and two masts. Nanny and Wenna come with us in the train to see us off at Plymouth. Nanny hugs us all, but when she hugs Mam she says the strangest thing. ‘I feel like I’m burying you,’ and she bursts into tears as if she thinks we are already dead. A horrible thought strikes me. Nanny must think she’ll never see us again. It makes my eyes tear up too.

‘It’s a good opportunity for us to go to Australia,’ Da says.

Nanny sniffs. ‘That may be so, but I will still have my tears, and be keeping ye all close in my heart.’ She puts her hands on either side of Mam’s face. ‘Every single day, I’ll be praying ‘ee’ll be safe and won’t be lost or attacked in that dangerous wilderness.’

Elowen and I stare at her.

‘It’s 1911,’ Da says. ‘It’s different now. Safe,’ he adds, as if he’s trying to make us all feel better.

Then so suddenly it all happens – a horn blows – and we can’t even hear what Nanny’s saying from the noise of it. We get pushed up the gangway and I look

back to see Wenna crying. Nanny’s waving a white handkerchief but she can’t see me waving back: she’s looking in the wrong direction. The tears are pouring down my face by the time we reach our cabin.

‘Krenza’s crying,’ Kitto chants in that horrible boy way.

‘Be quiet.’ I say it loudly and Elowen cries too.

Mam says nothing. Her face is closed tight as if opening a chink will let all her tears fall out.

The cabin is tiny, and already Kitto is pacing like a dog on a chain. Da tells me to take him up on the deck.

‘Don’t be losing sight of him,’ Mam says as we go out the door.

After climbing lots of steps, we reach the deck and Kitto races to the railing. I shout at him to stop, but it does no good – he climbs it. I don’t like looking after Kitto. What if he falls overboard? I stand beside him, hanging on to his braces.

The next morning I tell Kitto, ‘I won’t take you out again if you climb the rail.’

He races over to it but this time he just puts his hands on it. He slips me a defiant look. ‘You’re as bossy as Wenna.’

I look out to the ocean and imagine those waves rising higher and higher with snapping teeth soaring over us. The ship would be swamped like a paper boat. Just then I heave my porridge over the side and Kitto laughs so hard he nearly wets his pants.

Life on the ship is run by a bell. It rings when it is time to wake up, or to eat in a long room with lots of other people, and to go to bed. It even rings for lifesaving lessons that a young sailor gives on the deck. Hundreds of people are listening; there’s hardly room to move. ‘These are the life buoys,’ he says, holding one above his head. ‘If you fall overboard we will throw you one to hold on to.’ He shows us how to help people breathe again if they fall in the water. Elowen gasps and I squeeze her hand. ‘If there is a storm, you must stay below deck.’ The sailor says it so sternly that no one says a word, not even Kitto.

I hope we don’t have a storm.

One night I wake and the bunk feels like it’s swinging more than usual. When I stand, I can’t keep my balance, so I put my hand on the mattress to steady myself. I can feel Elowen’s legs. The ship is making strange noises, not just the usual throbbing, more like groaning. I stumble and I clutch hold of Kitto’s top bunk so I don’t fall, but he’s not there. He’s probably using the latrine, but Da will throw a fit if he gets lost. I leave the cabin and go up the stairs to the latrine and call for him, but he doesn’t answer. I stagger up the rest of the steps to the deck. I can see him – he’s standing at the top of the steps staring upwards. I reach him and throw my arms around him. ‘What are you doing up here?’ We are pushed by the wind and the movement of the ship.

‘It’s a storm, see.’

I look up and see a huge wall of black water. It’s much higher than the ship and it’s curling over. ‘That’s going to fall on us! Come on.’

Kitto doesn’t budge. ‘It’s like Granda’s stories. They were true.’

I can’t watch any more, and I pull Kitto down the steps and shut the door behind us. The ship rises suddenly and we fall in a heap on the corridor floor. ‘We have to get to our cabin, quickly.’

‘Do you think we’ll die down here?’ he asks.

‘Of course not, we’ll be safe in the cabin.’ I hope I’m telling him the truth. That wave looked monstrous, as if it could smash the ship like a giant’s hammer. Inside the cabin, Da is waking and he sees me shut the door. ‘Where were you two?’

‘Kitto needed to pee.’

Da gives Kitto a stern look. ‘There’s a storm tonight. Use the po under Mam’s bed.’ He doesn’t sound worried, but I can’t get to sleep. What if the waves smash the sides of the ship and we end up in the water with no life buoys?

In the morning I take Kitto and Elowen up to the deck. Sailors are mopping up water, but there are no broken masts and the funnel is still intact. The huge waves have disappeared, and a piece of blue shows through the clouds.

‘What happened?’ Elowen asks.

‘There was a big storm,’ Kitto says. ‘Waves as high as the sky, just like Granda said. It was exciting, but Krenza is a spoilsport. She made me go back to the cabin.’

‘You’re not allowed on deck at night,’ Elowen says, and Kitto sticks out his tongue.

Each morning I count off the days on a piece of paper. It takes thirty-five days to arrive at Port Adelaide, and every day I wish Wenna was with us and every day I pray we don’t have another storm.

Cousin Jacob is the first person I see on the Port Adelaide dock when we walk off the steamship. I know because Da tells me. Cousin Harry is right behind him. Uncle Malachi is loud and tall, and Jacob is much the same. The first thing Jacob says makes me stare at him.

‘The ship Yongala hit a cyclone off the coast of Queensland. Sank overnight. Everyone drowned, all a hundred and twenty-two of them.’

‘That’s nasty,’ I say.

‘Yep.’ Jacob is enjoying himself, but I meant he was nasty, not the horrible news. I give him my scariest squint, but it does no good. ‘Only a racehorse survived. Moonshine.’

Uncle Malachi frowns at him. ‘That’s not the best conversation for people just off a ship, boy.’

Jacob is watching me, probably hoping I’ll cry. I push my lips together and look at Harry instead, but he won’t meet my eye. Jacob leans so close I think he’s about to pick up our carpet bag. He murmurs, ‘Two days ago it happened, on the twenty-third of March. You were still at sea. It could have been you.’

Elowen’s lip quivers, so I take her hand and try to ignore Jacob. It’s Harry who lifts the bag on to his shoulder as he walks off in front of us.

I keep bumping into Mam. We are all having trouble walking in a straight line. Jacob thinks it’s funny, and I think he’s mean.

‘You’ll get your land legs soon enough.’ Uncle Malachi throws his arm around Da. ‘I couldn’t wait till you came, Clemo. Twenty-five years is too long.’

Da nods as Uncle Malachi carries on. ‘Wait until you see the land. Virgin scrub for you and me to clear and grow wheat on.’

‘And me,’ Jacob says.

Uncle Malachi ignores Jacob. ‘I’ve got horses and two drays already. I even found you a wood oven.’ He glances at Mam. ‘Janna’s back with the younger ones but she’s looking forward to seeing you, Tressa.’

‘I be lookin’ forward to meetin’ her,’ Mam says, and I hear Jacob’s giggle. What’s so funny now?

We catch a train and our trunks are loaded. Uncle Malachi is enthusiastic in showing us things from the window. ‘See the lush farmland.’ He points. ‘Look how many sheep.’

The sheep are brown. There must be something wrong with them, and the land Uncle points out isn’t even green. Mam keeps quiet with Elowen in her lap but Kitto bounces on the seat. He’s like a fly in a jam pot. I keep thinking about the poor passengers on the ship that sank. It was what I’d been afraid of. I had nightmares of being sucked under the sea, the ship spinning around like a leaf in a bucket of water.

‘There’s such opportunity here, Clemo,’ Uncle Malachi is saying. ‘When would we ever have owned land in Cornwall?’

I stare out the window. There are no trees like ours, no streams, no white sheep. I loved to explore the woods at home but I never realised until now how beautiful they were.

Uncle Malachi doesn’t stop talking. ‘Adelaide’s been established for seventy-five years.’ He sounds proud, but Camborne has probably been settled for hundreds. We change trains in the town of Adelaide. It has horse-drawn trams like ours.

‘Those trees are the same as at home.’ Elowen’s pointing at half-grown oaks. Kitto sees an electric tram and hangs out of the window for a closer look.

‘We have electric trams in Cornwall,’ I say crossly.

‘There’s a motor car,’ Kitto cries. ‘And another!’ Motor cars are special, but I don’t say so.

It takes hours to reach a country area called Payneham where Uncle Malachi and Aunt Janna are staying. I’m so tired

it’s hard to be polite when we arrive, but Aunt Janna is nice. She seems too young to have a boy as tall as Jacob. She hugs Mam and takes her and Elowen to our room followed by toddley twin boys with thumbs in their mouths. A girl younger than Elowen watches us as her mother urges her to say hello. ‘These are your cousins, Mary Jane.’ Aunt Janna is still coaxing her as they disappear into the room.

I follow them. On the beds are wide-brimmed sunhats for each of us, even Da, and cool cotton dresses for Elowen and me, a skirt and blouse for Mam, shirts for Da and Kitto. ‘I thought it being winter in Cornwall you’d need something light to wear in our summer,’ Aunt Jenna says gently to Mam. Mam smiles with tears in her eyes at the kindness, and Elowen and I put the dresses on straight away. Aunt Janna is right: they are much cooler than our clothes. I put on the hat and find a mirror by the back door.

Jacob walks in with wood for the kitchen stove and sees me there in my Australian dress and hat. ‘You’re not Australian. I was born here,’ he announces. ‘My father came when he was fifteen, just a year older than me.’ He leans closer. ‘We’re the Australians, not you. You’re just a new chum.’

The way he looks at me is strange. I’m a Trevail with dark hair and brown eyes like him, so what does it matter if I’m not born here? I refuse to show that he upsets me.

At dinner Uncle Malachi says we’re leaving early in the morning. I can’t believe it. We’ve just spent thirty-five days on the steamship and before that a month packing and waiting – and now we’re expected to travel again! ‘I’ve been waiting so long for you to come there’s no point hanging about catching our breath,’ Uncle Malachi says, ‘especially since the Mallee is 160 miles away.’ I’ve never thought of such a long distance.

Before we go to sleep I say to Da, ‘I wish the railway went to the Mallee.’

He smiles. ‘That’s why it be called pioneering, Keren. We get to be making the tracks. If we was using the train we wouldn’t be pioneers a-tall.’ He kisses the top of my head. ‘Off to bed.’

Elowen and Kitto share the bed with me in Mam and Da’s room. They are fast asleep, and as Da walks in softly I pretend I am too. He sits on the mattress by Mam – the springs squeak – and I hear him speaking softly. ‘Janna isn’t coming to the Mallee until Malachi and the boys get it suitable for the little ones. A house built. Why don’t you stay here with the girls? I’ll take Kitto.’

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf