- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

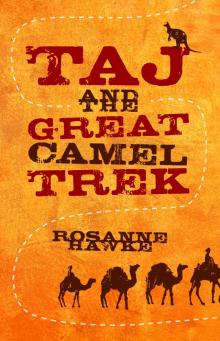

Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek Read online

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Map

About the Author

Also by Rosanne Hawke

For Allan and Joy Hawke

Camel Race

Choosing Camels

Mustara

The Expedition Sets Out

Camel Road

A Strange Thing

Port Augusta

Taj Rides a Goat

The Goat Race

Taj Has an Accident

The Elizabeth

Coondambo

Mustara in Danger

Wynbring

Tommy’s Big Water

The Camels are Lost

Youldeh is Born

Colona Station

Ooldabinna

Alec Finds a Dam

Return to Ooldabinna

Mr Giles’ Challenge

Leaving Boundary Dam

Arguing Over the Camels

Tommy Finds a Dingo

Youldeh

The Seventeenth Day

Taj has a Birthday

A Tornado Blows

Asad

Leaving Queen Victoria Spring

The Camels in Danger

Tommy Finds Water

Ularring

Pigeon Rocks

Ghost Boy

Tootra Station

Taj Receives a Telegram

The Expedition Reaches Perth

Afterword

Conversion Tables

Acknowledgements

Copyright

Rosanne Hawke is an award-winning South Australian author. She has lived in Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates as an aid worker for ten years. Her books include The Keeper, Soraya, the Storyteller and Mustara. She is a Carclew, Asialink, Varuna and May Gibbs Fellow, and a Bard of Cornwall. She teaches Creative Writing at Tabor Adelaide, and writes in an old Cornish farmhouse with underground rooms near Kapunda.

www.rosannehawke.com

Also by Rosanne Hawke

Marrying Ameera

The Wish Giver with L Penner, M Macintosh (illus)

The Last Virgin in Year 10

Mustara, R. Ingpen (illus)

The Collector

Soraya, the Storyteller

Yar Dil, E Stanley (illus)

Across the Creek

Borderland Trilogy (Re-entry, Jihad, Cameleer)

Wolfchild

Zenna Dare

Sailmaker

A Kiss in Every Wave

The Keeper

For Allan & Joy Hawke

In the Desert of the heart,

Let the healing start;

In the prison of his days,

Teach the free man to praise.

W H Auden

4 May 1875

Mr Giles and his explorers had come to Beltana to choose camels for their new expedition. Padar said a man had died on Mr Giles’ last trip into the desert. If they’d had camels they would have all survived.

We were having a camel race to show the explorers how good our camels were. I wanted to beat Tommy Oldham. Before he came to Beltana, Mustara and I had been the fastest.

‘Mustara! Hooshta, kneel,’ I said. Keeping the camels down at the beginning was the biggest problem. They never stayed on the line if they were left to stand.

Mustara kissed me on the head and gave a gentle moan before he folded himself to the ground. I glanced at Tommy. He couldn’t control his camel at all. He had Salmah, which was not a good name for her because it means submissive and obedient. She roared and tried to bite his leg but he managed to jump out of the way.

‘Tommy Oldham! Get that camel down,’ Mr Giles called from the side.

I shouted ‘Hooshta’ at Salmah. She swayed for a moment, then sat, grumping all the way down. Had I meant to help Tommy or to show him up? Lately, I hardly knew myself. Tommy grinned his thanks at me. He was a Wirangu boy from Fowler’s Bay who had been on Mr Giles’ last exploring expedition.

There were six of us racing: Mustara and I on the left side, Tommy next to us, and four of the Nunga boys from Beltana.

The Beltana blacksmith held the gun to start the race. He raised his arm. I tickled Mustara’s ears and whistled for him to rise.

By the time the gun fired, Mustara was up and racing out in front. He was light, not fully grown, yet he could beat the others. Soon Tommy on Salmah pulled ahead. She ran like the desert wind; I felt the stones rise up and sting us as she passed.

‘Come on, Mustara. Faster.’ Mustara’s muscles strained; we gained some ground. Out of the corner of my eye I could see Salmah. Tommy was slapping her rump with a stick, kicking her sides. I’d never seen her run so fast.

‘Faster, faster.’ Then we were in front. I could see Padar at the end. I could smell the dust; hear the dull thump of Mustara’s feet on the sand, the shouts from the onlookers. Among them would be Emmeline, squealing. She’d be so proud – we had to beat Tommy and Salmah.

Then a shadow flicked across our path from the left. I never saw what it was – a dog, or a child pulled hurriedly back – but it made Mustara falter. ‘Don’t stop, Mustara. Come on.’ But every second counts in a camel race. We couldn’t make up that second. Salmah finished half a length before us, so close Mustara could have bitten her tail.

There was Padar lifting Tommy’s arm high, saying what a good rider he was, especially for a beginner. Mr Giles patted him on the back. I sat on Mustara watching, until Padar noticed me. ‘Good riding, beta.’ I shook my head; it wasn’t good enough. If Mustara hadn’t been startled we would have beaten Tommy.

Emmeline raced over, her dress riding up her shins, her hat falling off. ‘Taj.’ She was breathless for a moment. ‘That was fun to watch.’

I said ‘Hooshta’ to Mustara and jumped off as he lowered himself to the ground. ‘We didn’t win.’ I was horrified that it was all I could say.

‘What does that matter? Mustara did well – all the riding we did in the desert helped him.’

I grinned at her. Emmeline could always see another side. ‘I suppose it did.’

‘Come home with me. Mama’s made honey biscuits.’ in the tin oven.’ Emmeline was the manager’s daughter and my friend. She was twelve and, like me, she had no sisters or brothers so I was often invited to her veranda for afternoon tea.

‘Mustara can take us,’ I said. We both climbed on, Emmeline in front. I whistled and Mustara rose to his feet in one fluid movement. I loved the way he did that. Emmeline clutched her hat and laughed at the sky. She loved Mustara almost as much as I did.

When I had eaten three biscuits I said, without looking at Emmeline, ‘Tomorrow the explorers will choose the camels for the expedition to Perth.’

She didn’t say anything and I looked up. She had her bottom lip between her teeth. She always did that when she wasn’t sure what I’d think of her words. ‘You truly want to go, don’t you?’

I tried not to look too excited and just nodded at her. I couldn’t tell her how wonderful an exploring expedition would be, or how lonely it was in the hut the last time Padar went with explorers. She’d say I still had her but she wasn’t there at night time. Besides, I wanted to be with Padar and that is what I said. ‘It wou

ld be good for Padar and me to be together on an expedition. Around here we don’t talk much.’

Emmeline stared at me. An image of her and her father came to mind – a picture of him lifting her up and laughing, hugging her as she told him details of her day. All the things Padar didn’t do to me anymore, not since my mother went. Padar and I needed to talk about it but I didn’t know how to begin.

Then Emmeline said something we’d both been frightened of discussing. ‘Mustara is not as big as the other camels. Why would they choose him?’

‘He’s strong now. We’ve taken him into the desert so many times. I could ask Padar to–’

‘Would you go without him?’

My mouth opened in horror. ‘Without Mustara? How could you even think of such a thing?’

She leant forward and her look was kind. ‘Just be prepared – if they don’t choose him, you will have to stay.’

The next morning I found Padar checking Salmah’s legs. ‘Is she all right, Padar?’

He smiled at me but his eyes were dull. For almost a year now his smiles had lost their sparkle. Were mine like that too? ‘Yes, the race didn’t affect her.’ He gave her a rub on her belly, but Salmah just grunted in bad humour. It was very hard to know what would make Salmah happy. I started on my carefully planned idea with Padar.

‘Padar?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Could you tell the explorers what a good camel Mustara is? Then they’d choose him today. They’d trust your judgement.’

Padar turned from Salmah to look at me. ‘What are you saying, Taj?’

‘I want to come with you. I want Mustara to come too.’ I sounded like a little child and wished I didn’t. ‘I can help you with your work. I can fix the saddles if they break, check the camels for sores. I can catch them in the mornings. I would be a help on the expedition and so would Mustara. He could carry something.’

Padar put his hand on my shoulder. ‘Taj.’ Then he shook his head. ‘Mustara is not fully grown. They will not take him. They need adult camels to do the carrying. It will not be a picnic in the desert like you have with young Emmeline. It will be hot, then cold. Maybe there will be no water. Maybe some camel will die. Do you want this for Mustara?’

I shook my head miserably.

‘Emmeline’s mother will look out for you, so will Bill the blacksmith. He has what he calls a soft spot.’ Padar smiled, but I couldn’t. Then he sobered. ‘Camel driving is my work, Taj. It is what I have always done even in the old country, and it means I have to go away from our home at times to care for the camels. This way I earn money for our life here, and you are old enough now to be looking after yourself.’ Padar touched my head and moved on to check the bulls, Malik and Rajah. I watched them darkly. They were magnificent camels, growling in fun at Padar; there was no doubt the explorers would choose them.

I sat with Mustara snuffling down my neck until the explorers came out to the yards. I watched them through narrowed eyes. Mr Giles was the leader, though he wasn’t the tallest. He had wispy, light-coloured hair and a dark moustache. He had hair on the sides of his face too. Padar let his beard grow all around his face wherever it is meant to grow, but the English shaved it off in peculiar places. Mr Giles spoke a lot to a taller man with an odd beard shaven off at his chin. Another tall man with hair the colour of henna walked like a soldier and had much to say about the camels. Mr Giles called him Jess and seemed to listen to him. What would they know about camels? They should be listening to Padar.

They came closer as they checked the camels; Mr Giles patted some and said straight away, ‘That one.’ He conferred with the other men about some. Salmah was one of those. She roared at them, and the man called Jess jumped. I grinned a little. Padar told them what a strong camel she was. Difficult in personality, yes, but she made up for it in other ways. ‘She is survivor,’ Padar said, and Mr Giles nodded.

A young explorer walked ahead towards me. He looked too young to be on an expedition; he was tall and almost as gangly as I was. ‘Gangly’ was Emmeline’s word. You’re gangly like a spider, she said to me once. ‘Good morning.’ The young one had stopped in front of me. He smiled at Mustara. ‘Is this your camel? He is very fine.’ Then he leant down and held out his hand. ‘My name is Alec, Alec Ross.’

I knew I couldn’t be angry all morning, not when this Alec said Mustara was fine; I stood up and took his hand. ‘I am Taj. Your camel driver is my father, Saleh Mahomed.’

Did Alec hear that note of bitterness I couldn’t conceal? He paused only a second. ‘Will you be joining him? I’m sure you will be a help with the camel work.’

I couldn’t answer for I was thinking how strict Padar could be when he had made up his mind. Alec was distracted by the other explorers then. They walked straight past me, men important with the power of choosing the best. I’m sure Mr Giles didn’t even see Mustara, how strong a bull he would be when he was full grown and what a pleasing personality he had and so easy to train. How could they know? They didn’t ask. Padar gave me a quick look but he was soon busy with Mr Giles, describing the strengths of Malik and Rajah.

When they’d all gone, Emmeline found me. She didn’t ask what happened; she knew. Mustara was trying to cheer me up with kisses on my head. ‘Nobody wants us today,’ I said. I meant it as a joke but it didn’t come out that way. I wasn’t good with joking.

Emmeline’s voice was over bright, like her eyes. ‘That’s not true, Taj Saleh, and you know it.’

I sighed. ‘I’ll take Mustara for a ride. It will make us both feel better.’

‘Then I’ll come too. I have my hat today.’ Emmeline grimaced at me. She hated her hat but her mother made her wear it. She tied the ribbons under her chin while I said ‘Hooshta’ to Mustara. He knelt beside us as we both clambered on. At my whistle he rose, so effortlessly. If only the explorers could see him now. I turned him by the nose rope towards the desert.

Emmeline sat in front of me. ‘Oh, it’s so high up here, I can touch the sky.’ Then she laughed. Emmeline’s laugh was so deep and infectious I couldn’t stay as sad as I wanted to be, and I urged Mustara into a gallop.

We ventured further into the desert than we had ever gone. Emmeline made me sing and Mustara lifted his feet as if he was dancing. I forgot about Padar leaving without me, and paid no attention to the sky. It must have been hours later when I first noticed it. ‘Oh no.’

Emmeline twisted around. ‘What is it?’ Her face changed when she saw the peach-tinted clouds looming behind us, like a mountain in a mist.

The wind had blown up hot for the time of year. Already grit filled our eyes.

‘Dust storm.’ I shouted for Mustara to kneel. The wind was stronger now, pulling at my turban and Emmeline’s hat, and we only had time to hide behind Mustara. I looped the reins over my arm and clung to Emmeline.

The dust was so thick I couldn’t even see her. ‘I can’t breathe,’ she shouted; there was more but the words were taken by the wind.

‘Don’t talk.’ The wind screamed above us and we hid our faces in Mustara’s fur. The air around us was grey as night. The cloud blotted out the sky, and we gripped each others’ hands so we wouldn’t blow apart.

Finally the dark wave rolled over. We spat dust from our mouths and rubbed our eyes free of grit.

We mounted as I whistled; Mustara blinked his eyelids clear and unfolded himself.

I felt as though I’d been deeply asleep and all looked different as I woke. We both stared about us, bleary eyed.

‘Which way is home?’ Emmeline asked.

Every way I looked there was freshly swept sand. I couldn’t see the sun for the dust haze and all our tracks had disappeared.

‘What shall we do?’ Emmeline peered into my face. Did she suspect I also didn’t know? Then she gave a laugh that sounded more like a cough and ripped the ribbons from her hat. ‘Father told me how explorers tie themse

lves onto camels’ backs when they are sleepy or unwell. Here, we can use my ribbons.’

I think she was joking. It was Emmeline’s way and I almost cried to hear her courage. She was like a mountain lion. That was what Mustara was too, an Afghan mountain lion. It is what his name means.

I managed a smile. ‘It’s a good idea but the ribbons aren’t strong enough. We’ll use Mustara’s reins instead. He’ll find the way home.’

She grinned at me as if to say ‘Of course’, but I hoped Mustara could do what I expected of him. If not, we were truly lost.

Emmeline’s songs had dried up with the dust, but we both tried not to say discouraging things to each other. I was thinking them though and maybe Emmeline knew, for every now and then she’d lean back and poke me.

‘What are you thinking, Taj?’

‘Nothing,’ I said.

‘Then tell me a story.’

I didn’t feel like telling stories either but I knew Emmeline would keep asking so I told her one about seven princesses and seven princes who lived in Persia. She liked stories about princesses and the more of them the better. Padar had told me stories ever since I was a little boy, though not lately. Strange that my mother didn’t tell me stories, or not that I remembered.

‘What shall we do when it gets dark, Taj?’

I shrugged. ‘We keep going. Mustara can walk in the dark.’

Emmeline was quiet then and so was I. We watched the muddy sky as Mustara plodded onwards. It was still too hard to see which way the sun was travelling; I could only trust that Mustara knew the way.

Dusk had fallen when I began to recognise shrubs we brushed past. It was Alec and Tommy who found us first. ‘Ahoy there.’ That was Alec. He rode up on Reechy, a new white camel. She gleamed in the dark. ‘Everyone’s looking for you – the station hands, your fathers, the explorers.’ Alec sounded kind and I could see Tommy’s white smile as though it glowed. Then we were surrounded.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf