- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

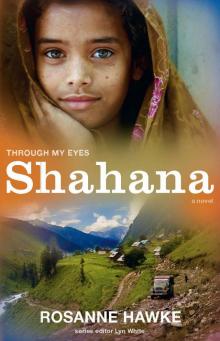

Shahana Page 5

Shahana Read online

Page 5

Chapter 9

When Shahana arrives home the boys are gone. So are Rani and the Lee Enfield. She purses her lips. Zahid doesn’t seem to go anywhere without the rifle. She sweeps the house on her haunches with the hand broom, as her mother did, and makes dough for bread in the morning. Then she takes her scissors, the string and a bagging needle and goes under the house to start work on the net. She knots lengths of the green string over the holes. The string is thick and rope-like. She hopes the fish won’t notice the shine on it. Nana-ji said anything strange in the water could scare them away.

She works quickly and has finished by the time Tanveer and Zahid come back with a basket of firewood. Tanveer unloads it to stack under the house while Rani tries to eat the net.

‘No, Rani.’ Shahana shoos her away.

Zahid squats beside Shahana. ‘You are very skilful.’

‘We are a family of stitchers.’

‘Of nets, also?’

Shahana shrugs. ‘Stitching is the same wherever you do it.’ She cuts the final threads from the knots. The net looks as strong as ever.

Tanveer says to Zahid, ‘We’ll catch a fish in the morning.’

Shahana suspects Tanveer wants to show Zahid how well he can fish. She reaches into her pocket and hands Zahid the small paper bag.

He opens it. ‘Saag seeds.’ He looks up at the sky. ‘It may be too late, but if we plant them in a sheltered place they may survive.’

Zahid takes Tanveer to a warm patch of ground near the house and gives him the spade Nana-ji used for snow. ‘Dig,’ he says, just like an older brother.

Shahana smiles at them. It is freeing to have someone else do things with Tanveer. She sits in the sun with the silver thread. The sun catches its facets and shines in her eyes. Pure silver. How she has wanted to work with silver. Will she ever get to embroider with gold? Wedding dupattas all have gold thread around the edges. Maybe Mr Nadir will give her gold next. But the thought of Mr Nadir and wedding dupattas wipes away her joy. The sooner she finishes, the sooner she will have to see Mr Nadir. What if he speaks of marriage again? What will she do? This house of Nana-ji’s is theirs now – hers and Tanveer’s. It is not as grand as Aunty Rabia’s with her tin roof, two rooms and window, but as Nana-ji always said, the sparrow feels comfortable upon the thorn bush. This part of the forest feels like their country. How can she leave it? Mr Nadir didn’t say where the man comes from. What if he lives far away? If only she could make money some other way and never see Mr Nadir again.

She threads the needle and watches how the silver thread sparkles as she pulls it through the pheran. Her mother’s voice plays in her head. Do not worry, the one who worries a lot rots. Enjoy the moment. Did she worry as a child? Is that why she can remember her mother saying this? What would her mother say now? There is so much more to worry about.

Shahana loses herself in stitching the winter branches of the chinar trees and the leaves lying on the ground in patterns – pure silver, just like snow in the sunlight. She shivers as a wind springs up, straight from the snow on the mountains.

When the boys have finished planting Shahana packs up her sewing and goes inside to heat the dhal and bread.

The next morning the boys take the net. They go early, so Shahana milks Rani and carries the bucket inside. When she emerges with her sewing there is a young man standing outside, petting Rani. Shahana stands very still by the door and carefully lifts her shawl over her head, but he has seen her. He looks like a militant; he carries a gun, an AK47 Kalashnikov, and wears a turban. He doesn’t wear a vest, just a plain shawl, like a blanket, not like Kashmiri clothes at all.

‘I heard your goat,’ he says.

Her heart thumps; he must be a militant. She has never seen one this close. When he lifts his head she sees he is the age Irfan would be now. She berates herself for seeing Irfan in every stranger.

‘What do you want?’ she asks in Urdu, wishing her voice didn’t waver.

‘I want some milk. I will pay you.’

She dares to argue. ‘I need the milk for my little brother. I cannot give milk every day.’

‘I won’t come every day.’

Shahana senses he won’t leave without the milk. Will he hurt her if she refuses? She wants him gone before the boys return so she disappears inside, leaves her sewing on the charpoy, and pours some milk into an old Sprite bottle. Her hands are shaking so much she spills some. She walks halfway down the logs and stretches out an arm so the man can take the bottle, then she retreats up the logs again. He doesn’t move, yet she can’t relax.

‘How many brothers and sisters do you have?’ he asks.

Shahana thinks carefully. Is he asking for information? Or is he just being polite? What if he returns to take Zahid and Tanveer for fighters? How young do they take them?

She tells the truth. ‘Two brothers. One died.’

‘I am sorry to hear one died. How old are the other two?’

She lets him believe she has two brothers left. ‘One is nine years.’ Too young, she feels like shouting. ‘The other is’ – she hesitates – ‘fifteen.’ She is not sure how old Zahid is. There is so much about him she doesn’t know.

Suddenly she realises what she must do. ‘Janab, if you see them in the forest can you please protect them?’ She suspects this young man is Pukhtun, from the same tribe as her father’s mother. They protect orphans and live by a code of honour; once you ask them for protection and hospitality they will not kill you.

He hardly pauses. ‘Zarur, certainly.’ He hands her five rupees. ‘I am sure you can use this.’

It is almost as much as Mr Nadir gives her. The young man doesn’t smile. Shahana’s father said the men in his mother’s family rarely smile at strangers, and especially not at girls who are almost women.

‘Shukriya.’

‘You speak Urdu?’ he asks, even though he can hear she can. But she knows why he is asking: only people who have gone to school speak Urdu.

‘Ji, janab, as well as Pahari.’ Then she adds, ‘My grandmother spoke Pukhtu.’

His eyes glisten for a moment and she thinks he will smile, but he keeps control of his face. ‘Khuda hafiz, may God be your protector,’ he says formally with a slight nod. He gives Rani one last pat and strides off. Rani bleats and starts after him until Shahana calls her back.

Now what is she to do? Relief that he left without hurting her makes her legs weak. She slides down the wall onto the logs outside the door. If she tells Zahid, he will ask everything and find out what she has told. But what if she doesn’t warn him, and then the militants come to take the boys away? Was Mr Pervaiz telling the truth about that? The young man didn’t take her away as Mr Nadir had warned.

If she tells Zahid, he will leave. She knows this as certainly as she knows that winter will enclose them. Maybe the young man is just lonely for his family and wants milk to remind him of home. Maybe it is only milk that he wants.

Shahana is too troubled to concentrate on her sewing so she goes inside and packs it into her backpack. She walks to the door, looks out, then walks back to the bed. She does this many times and then she decides.

She will try to speak with Ayesha.

Chapter 10

Shahana walks slowly up the steps to Aunty Rabia’s door. She calls out, but there is no sound from inside. Why did she think today would be any different? Because she saw Ayesha at the door? Because Ayesha had looked at her for a long time? It had meant nothing after all. Shahana returns to the road and heads towards the log bridge. How foolish she was to come.

‘Shahana!’

Shahana doesn’t hear her name at first.

‘Wait! Shahana . . .’

She turns. Ayesha is hurrying after her as quickly as decorum will allow. She is wearing a black burqa but she has the veil up. Shahana runs towards her. Just before they hug, they stop and stare at each other’s faces. It has been so long. Shahana kisses Ayesha on both sides of her face.

Ayesha says, ‘I didn’t thin

k you would want to speak to me again.’

‘Why?’

‘Because of our trouble. Your father was well respected and now is a martyr, while people say bad things about mine. They say he ran away.’

‘Do you think my parents would mind about that?’

Ayesha shook her head miserably. ‘My mother is so unwell. She is the one who doesn’t understand.’

‘Does she know you are here?’

‘Nay, she is resting so I haven’t long. When she wakes she will expect me to be there, or she will…’ she hesitates, ‘worry.’

Shahana wonders what Ayesha almost said but she grabs her hand. ‘Come into the forest,’ she says, and guides her over the log bridge.

‘Do you go out much?’ Shahana asks when they are sitting under a chinar tree. All the leaves have dropped; they can see the sky through the branches. Poplars nearby look like straw brooms sweeping the sky.

‘Nay, this is the furthest I have been. Of course we go into the garden at night, but Mr Pervaiz brings our food.’

‘It has been two years, Ayesha.’

‘I know, and I am sorry about your loss also. How are you living?’

Shahana pauses. She realises she can’t mention the militant after all. And Zahid? Should she say anything about him yet? Since he has come they have eaten better. Spiced hare has put colour in Tanveer’s cheeks. ‘Nana-ji taught Tanveer how to fish before he died. And I am embroidering.’

‘You? Sewing?’

‘Ji, Nana-ji taught me how to do that too.’ Then she adds in defence, ‘My mother sewed your clothes.’

Ayesha smiles sadly. ‘I know. I wish I could still fit into them. Ummie can’t sew or do anything anymore.’ She stops, as if she has said too much.

‘So you are cooking?’

Ayesha nods. ‘I do everything.’

‘Then we are the same, you and I, except Tanveer gets the firewood and fish. And he is learning to milk Rani.’ She stops as she remembers who is teaching him that.

‘Ummie is so sad, she doesn’t remember how to do normal things. She sits in a dream most of the time.’

‘Tell her we need her.’

Ayesha frowns. ‘She won’t understand.’

‘How can we make her better?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘What if I speak to her?’ Shahana says.

‘She hasn’t spoken to anyone in the village since Abu disappeared. Some people say he left to fight with the militants but he wouldn’t have deserted us.’

‘Maybe the police thought he was going to do that and put him in prison. Even if he is with the militants he would have been forced to fight,’ Shahana says, thinking of Zahid and Tanveer. Could Zahid help? His father has disappeared too.

‘We just need to know. It is the unknowing that has crippled Ummie.’

They are quiet for a moment, then Shahana says, ‘Ayesha?’

‘Ji?’

‘I think I am in trouble.’ Ayesha is a year older; surely she will know how to help.

‘What sort of trouble?’ Ayesha’s frown deepens. ‘You need money? We still have some left.’

‘No. I embroider for Mr Nadir and he pays me.’

‘Nadir Akbar’s cloth shop?’

‘Ji.’ Shahana takes a deep breath. ‘And I think he has made me an offer of marriage on behalf of a friend of his.’

‘But we come from educated families; we are too young to think of things like this.’

‘I know it. I have refused but I don’t think he believed me.’ Shahana holds Ayesha’s hand. ‘I am frightened to go back but I have to take my embroidery work to him. What shall I do? I need an adult to speak to him on my behalf.’

‘Finish the work and I will take it. I can say you are ill.’

‘But you don’t go out of the house.’

Ayesha nods. ‘If I have to go somewhere like today, I wear this.’ She pulls at the burqa.

‘But if you go for me the matter won’t be settled.’

‘It will give you more time.’

‘What if he has a proposal for you as well?’

Ayesha smiles. ‘I will say my mother has already decided on another. Besides,’ her smile fades, ‘no one will want a marriage with me until we find out what happened to Abu.’

‘Oh, Ayesha.’ Shahana hugs her. ‘I knew you wouldn’t forget our friendship.’

‘I never will, but I have to return now.’

‘How shall we know to meet?’

‘You can bring the sewing to the house. Ummie is used to hearing people come to the door. But to talk together?’ She stops to think. ‘You can leave a note under the door and I’ll come when Ummie is resting.’

When Shahana returns Zahid and Tanveer are under the house. Tanveer is showing Zahid how well he can cut up a fish. He is laughing. Zahid looks up as Shahana passes by. She wants to say they were a long time and ask what they were doing, but she has a secret of her own now and doesn’t want Zahid to ask about her day.

It is Tanveer who asks. ‘What did you do all morning, Shahji?’ Then he adds cheekily, ‘Did you miss us?’

It is a long time since she has seen him so playful. She smiles at him. ‘I stitched and—’ She hesitates. ‘I spoke to Ayesha at last.’

Tanveer moves his shoulders like a Bollywood dancer. ‘What good news. Is Aunty Rabia better?’

Shahana’s eyes feel cloudy. ‘Nay, but at least Ayesha is speaking.’

Zahid doesn’t ask who Ayesha is and Shahana understands something about herself and Zahid: people with a secret don’t ask many questions. Tanveer has no secrets and so asks questions all day.

‘Did you see anything dangerous by the river?’ she asks carefully.

‘Militants, you mean?’ Tanveer wipes his knife.

Shahana started. ‘I mean dogs,’ she says in a strangled voice.

Zahid says, ‘Only in the distance.’

‘There seem to be fewer dogs,’ Tanveer adds.

Maybe Shahana should tell them what Mr Pervaiz said about militants so Zahid could be on guard? But Zahid knows there are militants in the area. He saw them himself. Best to keep away from the subject altogether.

Zahid stands. ‘Will you give me a potato? Your oldest one. Tanveer and I can plant it.’

‘But we will need to eat it.’

‘With plants you have to think ahead. Sometimes you have to sacrifice one to have more food when you are in greater need.’

Shahana doesn’t think they will have one old enough for planting, but one is softer than the others. When she brings it out, Zahid shows her the white nodules.

‘See these? They will grow once put in the ground.’

‘Winter is beginning,’ Shahana points out.

‘Ji, but it will be safe until the snow melts.’

Chapter 11

Shahana was running through the forest, her feet skimming across the leaves that covered the ground. A man with a grey beard was chasing her. He called, ‘Stop, I will marry you.’

‘Nay!’ she cried.

She climbed right up the mountain where the giant fence shadowed the forest. At the top a young man in a white cap stood knee-deep in the snow. It was Irfan.

‘Bring me your little brother,’ he said, ‘and I will help you. You will have no more fear.’

Then his cap changed into a turban and his face flickered until it was Zahid’s.

Shahana springs awake. Rani is bleating to be milked under the house. Tanveer is nowhere to be seen, and Shahana wonders where he has gone without Rani. She checks under the house; Zahid has gone too, and yes, they have taken the rifle. She hopes the onions she has left will stretch to another hare curry.

She takes her sewing and sits on the logs outside; it is too cold now on the ground. She is thinking of Ayesha when she hears a man’s voice.

‘Assalamu alaikum.’

She looks up and sees it is the militant. He walks very quietly. Maybe they learn how to do that at the militants’ camp. She puts her needle

through the cloth and stands up. ‘Janab?’ She forces her face to stay immobile, even though the rest of her shakes like autumn leaves.

He has the empty Sprite bottle in his hand.

‘It is only two days,’ she says. Then she bites her lip. Will he think she is complaining and be angry?

‘I said I wouldn’t come every day.’

She has Zahid to feed as well. What if the milk doesn’t last? Well, she would go without. She is not sure what the militant will do to her if she refuses. Would he use the gun? She takes the bottle inside and fills it.

When she comes out the man is squatting by Rani and talking to her. ‘What is her name?’ he asks when Shahana hands him the milk.

‘Rani,’ she says.

‘I am not surprised, she is just like a queen.’

He is not so frightening, squatted by the goat. Rani is nibbling the tail of his turban and he doesn’t stop her. ‘I have a sister just like you,’ he says suddenly.

Shahana looks at him in shock. She thought he was going to say he too has a goat, not a sister.

‘Her name is Neelum, the same as your river. Every time I look at it I think of her. How brave and proud she is.’ Then he stares up at Shahana. ‘Like you.’

Shahana blinks. He is a militant. Men like him killed Irfan and her mother. She doesn’t want to hear about his sister.

‘She is your age and she likes sewing also.’ He glances at the pheran as if he wishes his sister were there, sewing it herself. ‘She attends school. Do you?’

His eyes are compelling and she tries not to look at him directly. She knows she has to answer him; he is too strong. Maybe if she answers his questions he will go away, up the mountain back to his camp.

‘My tent school was shelled. There is no school here now.’

He stands up and Rani playfully butts his legs. ‘Is there no one to teach you?’ He reaches out a hand to scratch Rani’s head.

‘The teacher is unwell. She is a half-widow.’

The young man nods as though he understands, but Shahana is sure he doesn’t.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf