- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

Daughter of Nomads Page 4

Daughter of Nomads Read online

Page 4

‘Did you apprehend the assassin?’

Azhar bowed his head. ‘He slipped away. Too many people were in the bazaar and I had the girls to attend to. I couldn’t let anyone else succour them in case they were the assassin.’

‘Nah kheir, no.’ Kifayat stood staring a moment, before switching his gaze back to Azhar. ‘Then there is not a moment to lose. It is time to deliver her to the mountains. It’s where she belongs.’ Then he added, ‘If she has been so protected she may be easy prey for the wrong people to manipulate.’

‘I need to take her to the Kingdom of Kaghan first.’

‘Why is this?’

‘Hafeezah became frightened when Jahani’s friend was killed and has told Jahani she is not her birth mother. Now Jahani is intent on finding her true family. I’m hoping this could lead her to her destiny.’ Azhar exhaled. ‘She seems the type of girl who would need to discover this herself. She may not believe it otherwise.’

Kifayat fell silent, thinking, then nodded. ‘It is best to travel in stages as she’ll need to be prepared; otherwise it may be too big a shock. This could play into our hands – she could gain support on the way.’ He turned to Azhar. ‘You have been a good son to me, obedient and respectful, but—’ he paused as Azhar frowned, ‘—this may be too big a task. You have barely seen eighteen summers. I am fearful for you, aziz.’

‘Pedar, I have to do this. Please, I beg you. Do not forbid me.’

Kifayat nodded sadly. ‘Very well, it is your destiny, but that doesn’t mean I have to be happy. Remember you must visit me regularly, so I know you are safe. And I will help you in any way I can.’

‘Mamnoon, thank you, Pedar.’ Azhar knelt to touch Kifayat’s feet and felt his father’s hand tremble on his head in blessing.

‘Be careful,’ he said as Azhar rose. ‘Do not let your youth draw you into trouble. And do not disclose her secret too soon; it may be dangerous for her,’ he paused, ‘and for us.’

Azhar sighed. ‘She is a girl of spirit. It will be difficult. What do I say when she asks who I am?’ He struggled to keep his voice even as he said, ‘She doesn’t know me, Pedar.’

‘You have grown and changed much since those days.’ Kifayat pulled aside a curtain. ‘Speak the truth,’ he shook his head slightly, ‘only do not yet reveal all.’ He indicated the room beyond. ‘Come. Sup with me before you return. The food is ready. We do not know when we shall have such a moment again.’

5

En Route to Mansehra Kingdom of Hazara Mughal Empire

Jahani, Hafeezah and Azhar rode off at sunrise before the day grew hot. No one waved goodbye. Jahani sighed. Even though her heart felt heavy, she couldn’t quell her curiosity about what they would see and do on their journey. She had never travelled outside the village of Sherwan her whole life. As far as she could remember, anyway.

Hafeezah had burned rue on a plate for them to inhale as they left the house. A spiritual blessing, Hafeezah said, to make their journey safe. She even dusted them with flour. Sameela’s family didn’t practise such customs, but Azhar hadn’t seemed to think it strange.

‘Today we will try to travel at least twenty miles or it will take a few days to reach Mansehra,’ Azhar said. He glanced at Jahani. ‘And please ensure the lower half of your face and your hair are covered with your dupatta.’

‘Who will see me on the road?’

Hafeezah took Azhar’s side. ‘It is to be safe. Someone may still wish you ill, especially if they know it was Sameela who was killed.’

Jahani pulled her dupatta up over her head and tucked one side across her face with bad grace. If she had a daughter she wouldn’t be so heavy-handed; she’d let her enjoy the smells of the countryside. Then she fell silent, thinking how Hafeezah wasn’t her mother anymore.

Jahani had enjoyed her short riding lessons with Sameela and her older brother, but it was soon clear that she needed more tuition to handle the saddle. After they left the village of Sherwan, Azhar rode beside her, coaching Jahani on how to balance on Chandi’s back as it rose and fell. It was nearly impossible with both her legs draped over one side as Hafeezah had insisted. But Jahani would bide her time. She was going to ride like Azhar with legs astride just as she had with Sameela.

After he was satisfied with her progress, Azhar rode ahead, and Jahani soon forgot herself as she took in the scenery of the open fields. Some crops waved golden heads in the breeze and men crouched with a scythe cutting hay. Boys tended sheep in another field. She even saw a blindfolded buffalo trudging in circles turning a huge waterwheel as water splashed into a canal.

The road grew congested with farmers and animals as they travelled further from Sherwan. She glanced at Azhar. He almost fitted in, but not quite. Even though he wore the clothes of a humble worker, except for his embroidered waistband, his bearing and the way he rode belied a peasant background.

Often they had to quit the road to allow a flock of goats or flat-tailed sheep to pass. Jahani observed the herdsman at the head of one flock. The sheep followed the sound of his voice. They had streaks of red powder on their woolly backs.

‘Why is the colour necessary?’ she said as they watched them pass.

‘In case they become mixed with another flock,’ Azhar answered simply.

Their mounts shifted their feet, tails flicking at flies. It was such an idyllic scene and difficult to imagine any danger.

That afternoon they approached a large group of people with horses, sheep, goats, a few camels and dogs heading to the north like them. It looked like a tribe shifting house.

‘Nomad shepherds,’ Hafeezah murmured. ‘They are called the “Lords of the Mountains”.’

The women wore colourful dresses over their shalwar and were unveiled, though some wore shawls slung over their shoulders. Their arms were covered by silver bracelets and huge silver studs adorned their noses. Colourful beaded necklaces hugged their necks. As they rode past, Jahani stared at them with yearning. She had never seen such people before, but she knew they would raise tents at night and would sit around their cooking fires eating chapattis and vegetable curries, telling stories and singing. How could she know these things? She watched as one woman led a flock of goats, and a boy beside her kept three dogs in line. A young child tied on top of colourful quilts was happily carried along by a pony.

Jahani’s dupatta fluttered from her face in a sudden breeze. In that instant she noticed a young man on horseback staring at her as the flocks walked past him. A white dog sat obediently at the horse’s hooves. The man’s hair was dark and wavy and fell to his shoulders. Jahani felt drawn to him, as if a vine stretched between them tugging them closer. His eyes were dark and, as he regarded her, his mouth fell slightly ajar as if in surprise. Too late Jahani realised her scarf had fallen to her neck.

Azhar loomed in front of her blocking the other man’s vision. ‘Cover your face!’ He sounded furious and narrowed his gaze at the shepherd, before urging Hafeezah and Jahani forward.

Hafeezah rode behind her and echoed Azhar’s words. ‘Do what he says. It may be dangerous for all of us if you are seen.’

Jahani adjusted her dupatta and narrowed her gaze. It was annoying how Hafeezah agreed with Azhar about everything. She was being treated like a child and she didn’t care for it.

As their mounts trotted away, Jahani glanced back. The young man still watched them closely.

Jahani reeled with fatigue in the saddle as they arrived at a caravanserai. Chandi trotted through a wooden gateway, and Jahani noticed stone rooms with curtained doorways facing a huge courtyard.

‘Rest for the travellers and security for the animals,’ Azhar said as they dismounted.

Azhar led their horses to a long stone trough of water where a few camels stood hobbled and eating weeds.

‘We will enjoy the caravanserais while they last,’ Azhar commented when he brought the horses back.

Jahani raised her eyebrows at him.

‘Where we are going,’ he explained, ‘there

are no caravanserais. These are only on the main thoroughfares. And personally, I won’t rest until we are in the more remote areas. It’s too easy here to be followed.’ He glanced around as if any one of the travellers setting up for the night could be an assassin.

Jahani shivered, but it wasn’t because of the cool evening air.

While Azhar collected sticks and made a fire with a flint stone, she helped Hafeezah take out chapattis and a pot of vegetable curry prepared the night before. They sat around the fire waiting for the curry and bread to warm.

Jahani’s back ached as she stretched. ‘Will it really take a moon to reach Zarah and Baqir’s home in the Kingdom of Kaghan?’

Hafeezah answered first. ‘I have not been back these nine summers. I barely remember how long it took to come.’ She glanced at Azhar.

With bread he scooped curry from the pot and tasted it. ‘It’s warm enough. Eat.’ When he’d finished a mouthful, he said, ‘It could take less time if we can travel twenty miles a day.’

Jahani groaned. ‘Is that how far we travelled today?’ She rubbed her back.

‘You’ll become used to it.’ Azhar ripped off more bread. ‘How are you, kaka?’

Hafeezah gave a weary smile. ‘No better than Jahani, I’m afraid.’

Azhar grunted. ‘We cannot linger here if that is what you are hoping. By the time we reach the Kingdom of Kaghan you’ll both be seasoned riders, jumping onto your horses.’ He gave a short laugh but Jahani winced, thinking of the uncomfortable saddle. The blanket hardly helped at all.

‘Maybe we should have brought a cart,’ Hafeezah murmured.

‘And be slower than ever?’ Azhar took a warm chapatti from the coals and passed it to Jahani. ‘Horses are less conspicuous and if we are pursued we can escape.’ Then he smiled at them. ‘Never fear, we will reach this place.’

Jahani watched his jaw working as he ate. How could he be so sure? She chewed her own bread thoughtfully, wondering if he could be trusted. Azhar was little more than a stranger to her. And yet she had to trust him. Otherwise how would she reach her destination? She couldn’t travel by herself as she had no idea where to go.

That night Jahani slept fitfully. As usual she dreamed, this time of camels and goats. She travelled with the herds along narrow mountain passes and over log bridges teetering across white rushing water. Glass and silver bangles covered her arms and she wore a flowing, multicoloured dress with pink shalwar. A white dog followed at her heels. She felt happy until a shadow loomed over her. A man took hold of her arms, pressing the bangles into her flesh; the glass ones broke and stabbed her. She struggled as he dragged her to a cliff. Water boiled around rocks far below. And then, he pushed her over the edge.

Jahani woke, panting. She wished she could understand the point of her dreams. She lay on a straw-filled mattress listening to the camels groan and spit and the horses stamping as they shifted around outside. Finally she pulled Sameela’s quilt around her and fell asleep cocooned in her memories of love and laughter.

The early morning saw them packing their few belongings after a breakfast of bread and chai that tasted of smoke. Hafeezah washed the few utensils they used, while Azhar secured the bags onto their horses.

Jahani stroked Chandi’s forehead and kissed her nose. The mare snuffled as though she were pleased.

‘You’re beautiful,’ Jahani whispered.

She giggled as Chandi nodded her head and kissed Jahani’s cheek.

‘We have a long day ahead of us,’ Azhar said to her. It sounded like he thought she was wasting time, and she scowled behind his back. As she mounted, her legs complained and she prayed she’d soon grow used to riding.

Their morning journey led them to the sprawling village called Mansehra. Native pines lined the road and she could see mountains in the distance, their foothills surrounding the huge village. Hay wagons drawn by donkeys or buffaloes jostled for a place on the road. Men shouted as they used a leather whip on their animals. Jahani wasn’t used to the noise or the odour of the animal dung. Hafeezah even draped her dupatta over her nose to hide the smell.

As they entered the village, Azhar pointed out huge rocks on the side of the road. ‘You’ve heard of Ashoka the Great?’ he asked Jahani.

She bristled. ‘Certainly. He ruled this whole empire over one thousand summers ago.’

He grinned as if he knew she was annoyed. ‘The emperor inscribed these rocks. I believe this is the oldest surviving writing of any kingdom.’

‘They look ancient,’ Hafeezah murmured.

Jahani dismounted and touched the inscriptions. It had been weathered for so long, she could hardly see it. ‘What does it say?’

‘That the emperor was sorry for the slaughter he caused when he overthrew this area and he would conquer only by righteousness from then on. He said it was his subjects’ duty to honour parents, relatives and friends, to give alms to the poor and to be tolerant of other religions. The final inscription says: Self control, respect, generosity and tolerance.’

‘Worthy ideals,’ Jahani said thoughtfully.

‘Are they possible though?’ Azhar watched her closely.

‘Perhaps if everyone followed the path of Qhuda consistently, they could show love to others.’

‘And how is it decided who is the true Qhuda? There are many religions.’

Jahani stared up at him, shocked.

His smile was wry. ‘Have you heard of the Angrez?’

Jahani nodded.

‘They say they worship the one true Qhuda,’ he said. ‘So who will argue the point with them?’

‘Then let everyone be free to keep their faith as they wish just as Emperor Akbar decreed one hundred summers ago.’ She thought for a while, then added, ‘Without being taxed for their difference.’

Azhar gazed over her shoulder as if seeing a person beyond. ‘You make it sound so easy,’ he murmured.

She turned to see who was behind her but no one was there.

They passed a bazaar and Azhar bought a hen. The hen squawked and flapped as Azhar tied it to Jahani’s saddle. Jahani soothed it in minutes.

‘You have a way with animals.’ He grinned at her and she could smell the fennel he was chewing.

Azhar was an enigma. At times he seemed unapproachable, but when he smiled he caught her unawares. She would have liked it better if he ignored her, then she wouldn’t have to think about him or wonder what his words meant. No other man had ever paid her special attention, so why should Azhar? He was just a guard and now their guide, after all.

Azhar bent over to check the straps under Chandi’s girth. She stared as a curl of hair slipped out from underneath his turban onto his neck. It was brown and looked like silk to touch. Jahani shook her head and stroked the hen instead.

That night in the next caravanserai, the fire crackled between them as they ate roast chicken. Afterward Jahani poured chai from a pan into cups, while Azhar explained to Hafeezah why caravanserais were built.

‘Some are centuries old, but just fifty summers ago the Mughal Empress Mehrunnissa requested more be built for travellers in the empire when she was the favourite wife of Emperor Jahangir. He loved her so much he ordered it so immediately. He called her Nur Jahan, the light of the world.’

Jahani recalled when Sameela’s tutor told them about Jahangir’s father, the Emperor Shah Jahan, building a beautiful monument to his love. It was called the Tomb of Light or the Taj Mahal. Sameela had said it was so romantic.

‘Just twelve summers ago Princess Jahanara, the sister of our Emperor Aurangzeb, built a caravanserai in Delhi,’ Azhar said, ‘to keep travellers safe.’

Hafeezah was hanging onto his words, but Jahani was suspicious. It was strange how he was just a guard and yet knew so many things. When a silence ensued, she asked, ‘How is it you can accompany us, Azhar? Do you not have a home or some form of other employment?’

Hafeezah’s eyes sparkled with interest in the firelight. Jahani glanced at her with worry – surely Hafeezah knew

more about him?

Azhar was silent at first, staring into the fire. Then he said, ‘My father released me to come.’

‘What is his name?’ Jahani asked.

‘Kifayat Ullah.’

Jahani expected him to say more, but there was silence until Hafeezah murmured politely, ‘A worthy name.’

‘And?’ Jahani prompted. She knew she was being impolite, even forward, but he should have told them these things.

‘He lives in Jask at the moment.’

‘So you don’t see him often?’

Azhar didn’t answer. He glanced at Hafeezah, but she seemed to be waiting for his answer as much as Jahani. He sighed. ‘It is a long way to Persia.’

‘Are you Persian? You don’t look Persian. Don’t the men shave their heads and sport moustaches?’

Finally Azhar smiled, but he looked nervous. ‘You are very inquisitive.’

Jahani glanced at Hafeezah but she didn’t admonish her, so she turned again to Azhar. ‘Well?’

‘Bey ya, no, we are not Persian. We have only lived there for some summers.’

‘So, you have come to Hindustan to find your fortune as Persians do, and my mother hired you.’

Azhar gazed at her, rolling his empty cup in his hands. After a while he said, ‘You could say that.’

By his tone Jahani knew he’d offer no more. At least she knew his father’s name. Strange it wasn’t Sekandar, like his. She tried her own father’s name again: Baqir. The thought of being reunited with her parents produced a fluttering in her belly and she decided not to complain about the saddle if it meant they could reach their destination sooner.

In the middle of the night Jahani woke suddenly. She’d heard a noise and strained to listen. Outside Azhar was talking calmly to Rakhsh to settle him. Had the horse heard it, too? Then there was silence. Jahani pictured Azhar on the doorstep of their little room – only a curtain between them. It felt strange to have a man sleeping so close that she could hear his intake of breath. Perhaps that is what it’s like to have a father or brother in the house. Jahani drifted back to sleep.

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

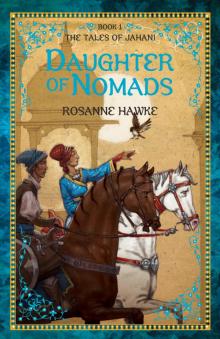

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf