- Home

- Rosanne Hawke

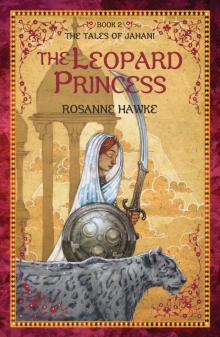

The Leopard Princess Page 10

The Leopard Princess Read online

Page 10

Tafeeq stood up. ‘I see.’ He paced while Rahul finished the curry.

Rahul glanced at Kamilah and she handed him a cloth. ‘Shukriya,’ he said kindly, and her face coloured.

‘We will allow our people to volunteer if they wish,’ Tafeeq said. ‘And I’ll send messengers to our sister tribes.’ He turned to face Rahul. ‘This is something you have passion for, so you will be the commander and I will watch the flocks.’ He smiled.

‘Shukriya, Abu. Thank you for your faith in me.’

‘Why shouldn’t I have faith in my only son? You will be chieftain soon. I am becoming tired.’ He strode outside and Rahul leaned against the carpeted cushions, exhausted.

Kamilah leaned forward. ‘I’m glad you have returned.’

‘You sound surprised.’

‘Ji, I didn’t think you would come back …’

Rahul frowned. ‘Why would you think I could leave my people? The tribe is my home, wherever we are.’

She looked up at him, her eyes filling with tears. ‘I’m sorry—’ She ran outside.

‘Wait.’ He hurried after her and stood outside, staring until she reached the single women’s tent. Neema was stoking the fire outside. She glanced at Kamilah, then saluted Rahul.

16

Alam Bridge

Kingdom of Gilit

Third Moon of Autumn

By morning’s light, Jahani’s captors had led her to a hanging bridge. To Jahani it looked even more dangerous than the one at Mazeno Pass. It was made with birch branches tied together with ropes, with another rope strung above to grasp while crossing. Already snow had collected on the wood making it wet and slippery. A river yawned far below. Jahani clenched her tied hands. If only she were free to brace herself when they crossed. Here she was – a shehzadi – and she’d never felt so helpless and defenceless in all her life.

‘This is Alam Bridge, which crosses the Gilit River to Skardu,’ the guide said. ‘It is the junction of the three great mountain ranges,’ he pointed as he spoke, ‘the Hindu Kush to the west, the Hemallehs to the east and the Qurraqorams to the north. See these rocks by the river? These are inscriptions of Buddhist monks from ancient times—’

‘Get on with it,’ growled the guard Jahani thought of as a barrel. ‘How will we cross this bridge?’ He spoke as if it were a curse.

The guide eyed him warily. ‘One man and horse at a time. It will be easier if we dismount.’

Both guards glanced at Jahani. ‘We’re not untying her,’ Barrel said. ‘She might jump. If we lose her our lives will be worth nothing.’

‘It’s true.’ The tall guard stuck out his skinny chest. Skinflint, Jahani thought.

‘Suit yourselves.’ The guide took Jahani’s reins and led both his horse and hers to the bridge.’

Protests came from the guards. ‘What are you doing?’

The guide didn’t even pause. ‘Do you want the girl to survive?’

Jahani turned in the saddle and saw the guards waiting at the edge, watching intently. ‘Any foolery and we will kill you,’ Barrel shouted.

The guide didn’t answer, concentrating on the other side of the bridge. Jahani tried to follow his example but, just then, her mount stumbled and slipped in the snow. Before the horse could regain its balance, Jahani slid to the left until she was almost hanging upside down from the undercarriage of the horse. She screamed. Roped on, she couldn’t right herself. Her hair swept the birch wood and through the gaps she could see snow sprinkling down to the river below. The white water raged, gobbling the flakes greedily.

‘Hold on, missahiba.’ Within a moment the guide was beside her, pulling her upright while the guards shouted angrily behind them. ‘Please excuse me.’

‘Shukriya,’ she said, glad he had dared to touch her.

Without pause, the guide continued leading both horses across the bridge. He strode quickly, making the bridge swing in time with her beating heart. She wished she could calm herself.

When they reached the other side the two guards crossed together, leading their horses. The guide muttered words Jahani didn’t catch, but, though the men walked slowly and their horses stumbled many times, they arrived safely.

They mounted, tipped their chins at the path and the guide continued to lead the way. With each bend they rose higher, and Jahani found it harder and harder to breathe. Her head ached so much it felt like it was being attacked with an axe. The wind grew so cold it bit through her cloak. She was glad for her furred hood, gloves and boots.

After a few hours the guide called a stop. ‘We’ll have to ride out the weather and carry on when it clears,’ he shouted. ‘We can shelter in a nearby cave. There’s not another for many miles.’

‘How long?’ Barrel asked.

‘A day, maybe more.’

Both guards grumbled as they dismounted and weighted their horses’ reins under a rock. It was the guide who untied Jahani and set her on the ground. She wondered if the guards would have left her out in the cold.

They followed the guide up the mountain side to a hidden hollow. Inside, the guide pulled kindling from the back of the cave, struck a flint and lit a fire; everything was waiting for him.

In the firelight Jahani could see the guide was younger than he looked. With his wild beard and hair he had seemed like a mad holy man, but his gaze when it rested on her was measured and clear. He handed her a piece of dried meat while the guards took chapattis from their packs. Skinflint offered her a piece with a lewd look. She hesitated, pulling her cloak tightly around her body; what would it mean to him if she accepted his food? Her hunger won and she took it. She would need to eat to survive the cold. The journey may take weeks and the horse she was riding was not a sure-footed Zanskari pony like Chandi. Only the guide had such a mountain pony.

After they ate, the guards motioned for her to sleep against the wall at the back. She lay under the blanket, thinking about how she could escape. The cave was not big. In one way this was helpful as it remained warm, but to go outside with the pretence of relieving herself would mean a climb over three men’s legs. What Jahani could do if she had Azhar’s carpet with her: she could flee these men. But would it fly in snow? Her thoughts were clouded by the betrayed look on Azhar’s face at the Indus River, then Chandi and Yazan filled her mind. Even Yazan wouldn’t be able to find her scent in the snow. She had lost them all and was totally alone.

Jahani dreamed of snow: cold fingers crawling up her legs, a weight falling on her like an avalanche. She snapped awake and tried to move, to call out, but there was a hand over her mouth.

‘Keep quiet, my pretty, and it will soon be over.’

In the faint light she could see the face of Skinflint leering, his body bearing down on hers. She struggled and managed to bite his finger. He whipped his hand away and slapped her.

She cried out and tried to reach Shamsher as the other men jumped up and hauled him off her.

Barrel punched Skinflint in the middle and he dropped to his knees curling over his injury.

‘Are you mad? Do you not value your life?’ Barrel ran his hand over his face. ‘If this is the right girl she is Muzahid Baig’s betrothed.’

The tall guard looked up, sullen. ‘When has Muzahid Baig ever done anything for us?’

‘He would find you, fool. Look, he has even found this girl.’

‘With our help and that rat-faced lying fraud at the border.’

The guide watched this exchange, then asked Jahani if she was hurt. He spoke in Burushaski and so gently it made her eyes fill, but she was determined not to weep in front of the guards.

‘Just my cheek hurts.’ She touched it carefully, studying the guide. Only a few people had ever spoken Burushaski to her: Hafeezah, Azhar, Ali Shah, Nusrat and now him. ‘What is your good name?’ she asked quietly, while the guards argued.

‘Hissam Sarwar at your service, missahiba.’ He hesitated as if expecting she would also say her name.

‘Are you from the Kingdom of Hahayul?’<

br />

He barely inclined his head but she caught the affirmation.

Jahani took a chance. She needed a friend, a supporter. She took a deep breath and whispered, ‘My name is Jahanara Ashraf Shaheen Khan, Shehzadi of Hahayul.’

He sat very still, but she could tell by his eyes that he was startled. ‘So it is true? There has been talk.’ He bowed his head and she quickly said, ‘Do not show you know.’ She pointed her chin at the guards. ‘I suspect they do not.’

‘You are coming to free us?’

She felt instantly colder. The devotion and belief in his eyes almost undid her. Who was she to give so much hope? ‘Only if I can escape Muzahid,’ she said more firmly than she felt.

His eyes hooded like a hawk’s, and he sat back just as Barrel kicked at the fire. ‘We will leave. The snow has stopped.’ Barrel glared at Hissam and Jahani. ‘You two look cosy. Remember, her betrothed will be upset if he hears we’ve been sheltering in a cave together.’ He indicated her sword. ‘Were you going to use that?’

Jahani stilled. ‘Muzahid would want me to be safe,’ she said softly.

He glanced at Skinflint then looked at Jahani, pursing his lips. ‘If I catch you using it, I’ll keep it.’

‘Could I ride without being tied?’ she asked then. ‘The ropes have bruised my wrists and Muzahid would be displeased.’

The guards stared at her incredulously. She held her breath, hoping she hadn’t overdone it.

Then Hissam said into the silence, ‘It is true that the ropes burn in the cold air.’

Barrel stepped forward and punched Hissam in the jaw. It was so sudden he fell backward. ‘She is our prisoner and we will make the decisions. Remember your place.’

‘She’ll escape,’ the other guard growled.

‘How can she do that? Where would she go?’ Barrel laughed and whipped around to face her.

She couldn’t stop from flinching.

‘You can ride without ropes, but if you cause any problem at all, you will be slung across the horse like a sack of flour and tied on. Do you understand?’

Jahani inclined her head. It was a small concession but a victory all the same.

Jahani lost count of the days and then the weeks. They travelled through wild snowy terrain with few trees, and had to shelter in hollows in the ground or on the mountain sides when it snowed. When it wasn’t snowing they trekked at a punishing pace. Hissam made their horses walk further during the mornings. ‘The snow is too soft in the afternoons,’ he said. They came across no other travellers.

She had plenty of time to think about the cost of her journey. She remembered the times she and Sameela wrote poems when they should have been learning their lessons. She thought of lines she would write if she had a reed pen. I will shape my face from a handful of dirt, and take one more step without feet. Taking steps without feet only reminded her of Azhar. If only I could unsee what I have seen, forget what I know to be true.

Jahani was constantly hungry. She salivated remembering how Rahul’s hawk or Yazan caught game for them to eat and how Azhar brought food – he always had a supply of resources. What she would have given to see Azhar winging the carpet toward her, rescuing her from this faltering horse. The horse stumbled on the track in ways Chandi never did. Once it staggered so close to the edge that Jahani saw the cliffs fall away far below; it was as if she were in the sky on Azhar’s carpet.

Hold on tight. Fool of a nag they gave you.

She started in fright. Where did that thought come from? She didn’t recognise the voice: it wasn’t Yazan or Chandi and certainly not her own mare. She looked ahead to Hissam. She could just see the rump of his stallion. Are you Hissam’s horse?

Awa.

But how can I understand you? I thought it was only my own animals who have the gift.

Those of us from the heavenly Kingdom of Hahayul know of you.

The kingdom. With her capture, Muzahid would gain the kingdom. She had to do everything in her power not to let that happen. But what?

One morning they woke and Hissam said a storm was imminent.

Barrel snorted, gesturing to the heavens. ‘You’re just saying that. Look, the sky is clear for once.’

Nothing Hissam said could persuade them. Instead, he was smacked across the face. Jahani watched it all as if from a great distance. Her head spun. She didn’t care anymore whether she rode or didn’t.

Later that day they passed a frozen waterfall, suspended as if time had ceased, and picked their way over a glacier. It was green. Jahani imagined she could see fish trapped under the ice; or was it a face?

Afterward the worst bridge Jahani had ever seen materialised before them. It stretched from one mountain ridge to another, crossing a narrow ravine. Jahani could see nothing but white snow below them, but she supposed that the Indus River was at least a thousand feet underneath. The bridge dipped in the middle and appeared to be made only of rope, though when they drew closer, she could see some planks of wood tied together as the base. Jahani took a deep breath but couldn’t clear the dizziness from her head.

‘It is the quickest way over the Indus,’ Hissam said when the guards questioned him. ‘But this time we must cross one at a time.’

Hissam went first, then Barrel. Jahani was next. She dismounted and led the mare. They were halfway when the horse baulked, causing the bridge to swing. Jahani tried whispering in its ear as she’d seen Rahul do to Farah. It helped a little, but their progress from then on was slow. The mare put out its hooves, feeling the way as if it were blind. Jahani exhaled when they finally reached the other side.

In the late afternoon, the echoing quiet around them seemed even more silent. Hissam continually watched the descending clouds. Then suddenly the blizzard hit. There was no shelter so they kept moving, Jahani following the rump of the horse in front. Soon she could see no one. She was so cold she had to imagine drinking chai by the fire with Azhar and Hafeezah to keep going. The memories swirled in her head as the snow swept around her and she held onto the horse’s mane in desperation. Suddenly the mare stumbled, and this time it fell. Jahani was thrown clear. She stood but all she could see was the driving snow.

‘Hissam!’ she cried. The wind whipped her words away.

He didn’t return, nor did the guards.

Eventually, she lay on the snow. She couldn’t move. Was this the end?

Azhar. Why think of him? He was already dead. Perhaps she would see him again soon.

Amidst the flurry in her mind she could hear something. A thought? Was it hers?

Shehzadi!

Hissam’s stallion?

The thought came again. Not one thought but two: Shehzadi! Shehzadi!

Chandi and Yazan. Never had they spoken at once before.

Shehzadi, where are you? Her mind clanged faintly as though they were far away.

In the snow … it’s so cold.

On the mountains?

Haramosh.

Do not sleep.

I am warmer now.

Keep awake! Shehzadi, do not sleep. Think of the kingdom.

Chandi asked, Do you have Shamsher?

Awa.

Hold the hilt with both hands. Do not let go. Chandi sounded just like a mother.

With her ebbing strength Jahani found the hilt of the sword beneath her cloak and rested her hands on it.

Think of your friends. Think of love.

The faces of Hafeezah, Sameelah, Anjuli, Zarah, Yasmeen and Rahul flashed through her mind. Her last thought was of Azhar as power radiated from the hilt; a stinging heat coursed through her fingers to her hands and up her arms. She cried out as the warmth squeezed into her frozen veins.

We know where you are now. Chandi’s thought tinkled like a goat’s bell.

We are coming. Do not let Shamsher go.

17

Muzahid’s Camp

Kingdom of Gilit

Muzahid paced outside his tent. He was trying to piece together the things he had witnessed: that skirmish at the

Indus; Jahani – for that’s who the warrior girl must have been – in those nomad clothes, her hair black, but no less comely; and the gypsy prince who was with her. He had been betrayed again!

Muzahid smacked a fist into his palm. He would kill the gypsy prince. Nay, he would cut him first, then disembowel him. If he cried out for mercy, only then would he cut off his head. He closed his eyes. There had been at least one hundred soldiers with the girl; his small troop didn’t stand a chance. But the soldiers didn’t look like nomads, so whose men were they?

Then the carpet. Weren’t flying carpets a myth? He scowled. What sort of person could fly one? A demon? Or a prince? Who was that young man who shone like the morning sun? He tried to quell his superstitious thoughts. It had to be some kind of trick. At least it was his own arrow that had felled him. Ha! See? Did demons die?

He smiled grimly as his captain approached. The man halted and waited for Muzahid to address him.

‘Any news?’ Muzahid said loudly.

The man flinched. ‘All your men have now arrived from Kaghan, sire.’

‘Achha.’ Muzahid scratched his beard. ‘We need a strategy. I have to get that girl. She is my betrothed.’

‘Ji, sire.’

‘We will go straight to the Kingdom of Hahayul. My army from Skardu can meet me at Haramosh Pass. We’ll ride in and shake up this Dagar Khan. He’s lorded over the north long enough. Now it’s my turn to control the Silk Route.’

‘Sire, there is a narrow mountain pass into the Kingdom of Hahayul. It is dangerous and known for badmarsh. Dagar Khan’s men may be manning it as well.’

‘Ha! We can overcome them all. Have some confidence, man.’

‘Ji, sire.’

Just then a scout raced up, but stopped when he saw Muzahid with the captain.

Muzahid waved him closer. It annoyed him how his men were so fearful. ‘Come closer, boy. What is it?’

‘I have ill news and good news, sire.’ The young man looked ready to flee, but the sight didn’t give rise to any kindness in Muzahid.

‘Then tell me, damn it.’

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll

Kelsey and the Quest of the Porcelain Doll Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal

Fozia and the Quest of Prince Zal Daughter of Nomads

Daughter of Nomads The Truth About Peacock Blue

The Truth About Peacock Blue Taj and the Great Camel Trek

Taj and the Great Camel Trek The War Within

The War Within Killer Ute

Killer Ute Shahana

Shahana Kerenza: A New Australian

Kerenza: A New Australian Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog

Jehan and the Quest of the Lost Dog Sailmaker

Sailmaker Zenna Dare

Zenna Dare The Leopard Princess

The Leopard Princess Dear Pakistan

Dear Pakistan Marrying Ameera

Marrying Ameera Finding Kerra

Finding Kerra Spirit of a Mountain Wolf

Spirit of a Mountain Wolf